a Weekly segment from Bruma Publications-PBBI-Fresno State.

50 years of the Carnation Revolution

By LINCOLN SECCO & OSVALDO COGGIOLA (Two Brazilian Professors)

In April 1974, this revolution began a process of dissolution of the state apparatus, the result of a workers’ and popular mobilization unparalleled in post-war Europe

Fifty years ago, in Portugal, the Carnation Revolution shook Europe and the world. In April 1974, this revolution began a process of dissolving the state apparatus, the result of a workers’ and popular mobilization unparalleled in post-war Europe. At the end of the year, US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger informed the authorities of the main European powers of the United States’ intention to invade Portugal to prevent the emergence of a “new Cuba” in the middle of Europe.

The extreme intervention of French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing prevented this, against a promise to contain the revolution by rebuilding the Portuguese armed forces. The Revolutionary War in Vietnam was the central event of this era; it ignited panic in the US about the worldwide spread of communism. Kissinger even put forward a “vaccine theory,” which should be applied in Portugal to immunize Europe against communism.

The Portuguese regime, installed in 1926 under the leadership of António de Oliveira Salazar and headed half a century later by Marcelo Caetano, had ended the sixteen years of the First Portuguese Republic. It was a corporatist-fascist dictatorship with a central role for the political police, the PIDE (Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado), responsible for repressing opposition to the “Estado Novo” regime, a peculiar Portuguese form of corporatism, installed in the decade that witnessed the rise of fascist movements worldwide, when, in Portugal, “the time of conflicts and class struggle would end in favor of the ‘national interest’, the only one to give cohesion to all.”

In Portugal’s case, this was not done through the creation of militias and brigades, as in the fascist examples, but through the state. First, through the Armed Forces, which were responsible for overthrowing the ‘anarchic republic.’ “Then through the repressive apparatus of the state itself in the vigilant action of its political police.”[i] The PIDE’s activity covered even the most intimate places of the Portuguese, such as family quarrels, but it intervened with particular force in labor conflicts. 200,000 people, 3% of the country’s population, worked in one way or another for the PIDE, which had an archive with three million files, equivalent to almost half of the Portuguese population. Portugal was, therefore, a police state. PIDE had 2,286 agents in 1974, but it paid between 10 and 12 thousand people, including informers. From 1962 onwards, the head of state granted daily audiences to the head of PIDE.

At the beginning of 1974, in February, however, the regime publicly showed its cracks with the publication of Portugal e o futuro by António de Spínola, by Editora Arcádia. The author, a military man and former governor of Guinea-Bissau, advocated a political rather than military solution to the colonial conflict after thirteen years of the “Overseas War.” The regime responded by dismissing Generals António de Spínola and Francisco da Costa Gomes from their General Staff of the Armed Forces positions. Marcelo Caetano asked the President of the Republic for his resignation, which he did not accept.

Just two months later, the Carnation Revolution started after a military action on April 25, which led to a huge popular mobilization and forced the government to resign. PIDE was abolished, and several of its main leaders were arrested. More than 1,500 arrests of PIDE/DGS members and informers took place between April and October 1975. At the end of 1976, their trials at the Military Tribunal began, with the judges being extremely benevolent towards the former PIDE members.

The beginning of this sequence was a literal implosion of the state, which paved the way for the start of a social revolution. In April 1974, the corporative state was dismantled due to the crisis in the Army, with its young officers forming the MFA (Movement of the Armed Forces), which was against the military hierarchy. The group’s motivation, initially called the “Captains’ Movement,” was opposition to the police regime and the Portuguese colonial war. These wars were the largest in Africa’s history.

The Portuguese military faced serious operational problems: there were three theaters of operations (four with Cape Verde). In Guinea: the plains of Senegal and Guinea Conakry. In Cape Verde: mountains. In Angola and Mozambique, guerrilla national liberation movements with popular support. Neo-colonialism clashed with the guerrilla insurgencies. Portugal could not abandon direct colonial rule in exchange for maintaining economic domination; it was an economically dependent country but with sources of colonial accumulation.[ii]

However, the military defeat in sight made the Armed Forces abandon their colonialist commitment and turn against the regime. For the military, it wasn’t initially a question of making a revolution but of a military coup to save their “dignity” against a government that was exposing them to a dishonorable defeat and the shame of being responsible for the end of the colonial empire. On March 16, 1974, officers left Caldas da Rainha to overthrow the dictatorship: the “Caldas Uprising”, however, failed.

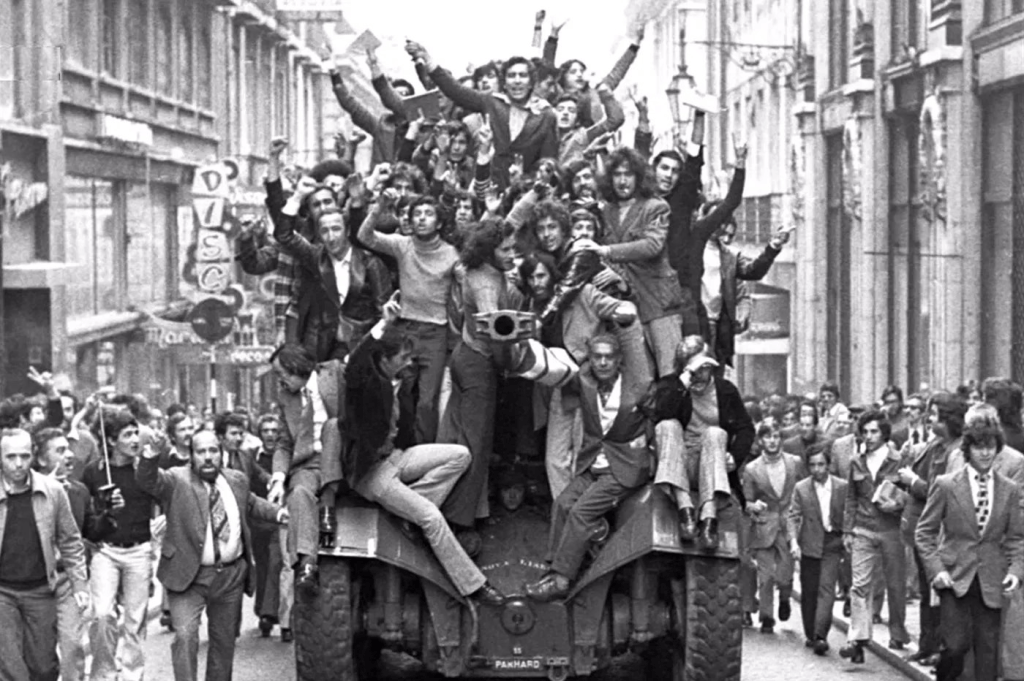

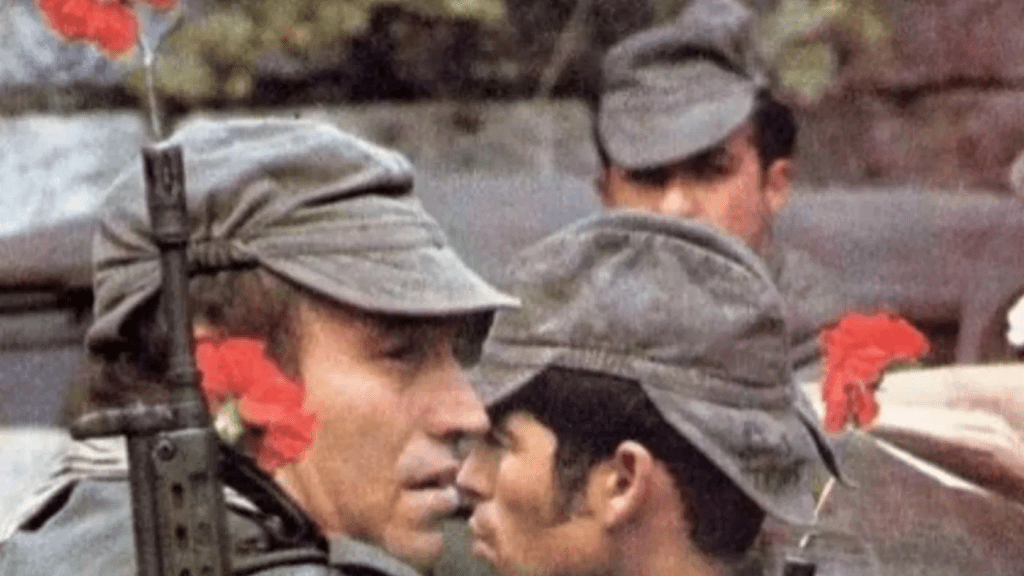

However, it showed the MFA officers that their only option was a coup d’état, and preparations began for the seizure of power. On April 25, Caetano’s dictatorship was overthrown in less than 24 hours, almost without bloodshed. Political prisoners were released from Caxias and Peniche prisons; PIDE, already renamed by Caetano as the Directorate-General for Security (DGS), was destroyed, as was censorship. Attacks were launched on the headquarters of the newspaper A Época, the regime’s official newspaper. The population destroyed the government’s symbols within a week, giving strong popular support to the MFA. The Armed Forces, former agents of repression, protagonists of colonial war, and defenders of the regime, seemed to be on the side of the exploited people, including the prospect of leading Portugal to socialism.

The decisive popular actions aimed to control the media and depose the government. The population took to the streets and changed the dynamics of the military coup, taking it beyond its initial intentions. Their actions (releasing political prisoners, occupying nurseries and businesses, purging universities) only had the support of the MFA because popular sanction was exactly what restored, in practice, the lost military dignity. However, the justification for the armed forces was regained by breaking the military hierarchy and disobeying the top brass.

This was the crucial problem with the Revolution: in the name of military dignity, it contrasted popular legitimacy with state legitimacy. Since the state apparatus was temporarily disorganized, only the population was enough for the MFA officers. However, this created a contradiction in the movement between the legitimacy of its actions and the Armed Forces hierarchy.

April 25 brought a wave of ideas and actions that were intended to go far beyond what the Junta de Salvação Nacional, which took power in the name of the Movimento das Forças Armadas, could (or wanted to) do. From vegetarians to Maoists, from homosexuals to ecologists, from feminists to Trotskyists, everyone was able (or believed they could) put their hopes into practice. The Maoist MRPP imitated the Dazibaos, which were huge Chinese posters with large newspapers on the walls.

The very walls of Lisbon were filled with large paintings as if the militants were in the middle of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Photographs of these murals show that they were made by various political groups. Publishers began releasing books that had been banned or recalled, translations that were ready but censored, and a wave of titles from the far left, from Mao to Guevara and Marx, essays on sociology, politics, and the overseas war, causing sales to suddenly rise by 60%.

Numerous grassroots organizations sprang up in civil society. Most of them around the revolutionary process. Ronald Chilcote wrote down 580.[iii] At least thirteen were political bodies made up of Armed Forces members, ranging from associations of ex-combatants from overseas to relatives of soldiers or officers on active duty or in the reserves. Official bodies such as the Armed Forces Movement itself, the Mainland Operational Command, and others were, in fact, political institutions of the Armed Forces. The 1st Artillery Regiment, for example, became known as the “red regiment” because of the support it gave to Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho’s actions.[iv]

Several actions affirmed the autonomy of the revolution’s social bases: the popular movement, which already, on April 25, occupied homes, nurseries, and political prisons; the organized movement of rural and urban workers, which often exceeded the limits imposed by their union and association representations; and the MFA itself, whose soldiers and low-ranking officers put the Army’s unity as the guarantor of order at risk. The popular movement was not the transmission belt of any party.

Charles Downs has shown that the political orientation of the residents’ committees, for example, had a radical or reformist political action due to their participation in mobilizations around basic problems that resulted in conflict with the government and not because of a prior orientation of extreme left-wing organizations.[v] The strikes exceeded the expectations of the MFA.

The strikes exceeded the Communist Party’s expectations, totaling 734 between April 25 and the attempted coup on September 28. In the Lisnave shipyards, where 8,500 people worked in the main plant (and almost 13,000 in the attached companies), the victories of the first strikes were spectacular. Partial strikes at Lisnave had begun in February 1974. Just after April, the workers obtained a minimum wage of 7,200 escudos and 5,000 for the canteen staff, who earned 2,500 escudos (a 100% increase). Apprentices were paid 6,800 escudos a month and 7,200 after six months. No pay rise above 15,000 escudos, and the reinstatement of all those dismissed for political or strike reasons. A total victory.

The workers’ struggle was also political: on February 7, 1975, the Lisbon workers’ committees called for a street demonstration against NATO naval maneuvers off the Portuguese coast. The demonstration was banned, but the soldiers who were supposed to monitor it saluted with their fists raised high. On May 15, a meeting of the MFA declared that the movement supported the February demonstration. However, the Council of the Revolution, after a six-day closed meeting, issued a declaration stating that the “dictatorship of the proletariat” and the “workers’ militias” “do not coincide with Portugal’s pluralist socialism.” The companies’ struggles and the factory councils’ emergence led socialists and communists and the MFA itself to try to control the trade union movement. The MFA coup had been prevented. Captain Maia, one of its executors, declared: “We had the feeling that we were heading for an abyss that would end in civil war, in which the people would arm themselves”…[vi]

The fundamental objectives of the MFA were summed up in the so-called three Ds: Decolonization, Development, and Democracy. Decolonization was the military’s main demand. It was about ending the empire and restoring the legitimacy of the Armed Forces. To do this, they needed to change their role: stop being the mainstay of the empire and become the basis for the transition from colonialism in Africa to some new “European” political role. National objectives conflicted with “imperial” ones since the main national institution needed to maintain its corporate integrity without losing the war. The war was already strategically lost. For this reason, the MFA proposed some kind of economic (and social) development that would replace the economy that had become the transmission link between the colonies and the central countries (Europe and the USA).

Although that economy was increasingly of interest to only a handful of colonialists who profited directly as owners of land and investments in Africa or as “transporters” or exploiters of African wealth, most of the nation found no safeguard in that structure. The development of the meager productive forces of a semi-peripheral capitalism tended to find its possibilities for subaltern expansion in Europe (and not in Africa).

For the central countries and the colonies themselves (whose foreign trade increasingly did without Portugal as a destination market), it seemed much easier to remove the colonialist veil that covered up the real exploitation of Portuguese Africa by international oligopoly capital to leave two clear ways out: the anti-colonial social revolution or adaptation within the framework of a “dependent and associated capitalism.”

Democracy was the inevitable corollary of the end of the empire. It was the antipode of the fascist dictatorship. As the political superstructure was the obstacle to another form of expansion of modern or capitalist relations of production (whether dependent on Europe or a socialist transition), democracy was the battering ram that would bring down the colonial empire. But which democracy? The chess pieces in the revolutionary process moved around its meaning. A “popular democracy” under the leadership of the PCP, a council democracy, the coexistence of direct and indirect forms of action, and a liberal representative democracy (with greater or lesser social content) were the main options (although not the only ones).

The three “Ds” imposed the strategic framework for revolutionary action. Within this framework, the political-military forces could establish their tactical maneuvers. However, the strategic framework not only imposes limits; it also opens up possibilities. The Revolution accelerates historical time in a space that suddenly becomes transparent. Options seem to be pushed to the limit, allowing us to see all the social contradictions. That’s why revolutionary processes broaden the political consciousness of millions of people overnight (or the other way around, in the case of April 25: literally overnight…).

Not only organizational pluralism but also that of ideas (especially those of the extreme left) entered the barracks. Thus, the Military Discipline Regiment was called “fascist”. The use of a single restaurant was generalized for officers and non-commissioned officers. Indiscriminately. This picturesque fact also revealed a spirit that could not survive without attacking the mentality that guaranteed military discipline. It was the ideology of “a democratic army.” With this title, the newspaper of the Armed Forces Movement intended to institutionalize a new understanding of hierarchy.

It was the institutionalization of the MFA itself, which defined itself as the “political vanguard of the Armed Forces” and now had its assemblies of unit delegates (ADU). These were advisory and support bodies for the command. By nature of his hierarchical superiority, the commander was the head of the ADU. He was also assisted by the delegates of AMFA – the Armed Forces Movement Assembly. But who was in charge?

“It should be emphasized that the ADU in no way calls into question the authority and decision-making responsibility of the command.” Meanwhile, “the commanders, for their part, should be the first militants of the MFA, always bearing in mind that the intention is not to restore an outdated military institution, but to create a new one, in the sense of moving towards a competent, democratic and revolutionary army, placed at the service of the people and capable of corresponding to the socialist society that is to be built” (Directive for the democratic structuring of the MFA in military units and establishments).

This persistent ambiguity between corporatism and political leadership, internal democracy and discipline, and tradition and revolution appeared in expressions, in words, in creative combinations: “conscious discipline and dynamic hierarchy,” “consented discipline,” “persuasion before order,” and “revolutionary will and discipline.”

What was being discussed was the “total integration of the Armed Forces into the spirit of the MFA,” which would occur through the “clarification and politicization of the Armed Forces.” At the same time, this document paradoxically spoke of a “high level of discipline, cohesion and efficiency.” Defining the MFA within the structure of the Armed Forces was just another of the Revolution’s impossible tasks. This would only be possible, it was thought, at the time when the MFA could be diluted in the Armed Forces as a whole, and there was a coincidence of political positions. In other words, “in the medium term”! An intellectual and ideologue of the so-called “group of nine”, Major Melo Antunes, questioned this ambiguity of which he was a victim and agent: “The current situation of military anarchy was, to a certain extent, the result of our mistakes, or more precisely, our illusions; we believed that a democratic political structure could be installed in the Army.”

The revolutionary military fed on poetry taken from the past, preaching some order, some hierarchy, and some discipline; in order not to break with what the Armed Forces were and could only be, they anxiously sought models, such as Velasco Alvarado’s Peru. They read articles about the Peru military coup and its nationalist and popular government. In the catalog of the publishing house Prelo, there was the book Peru: Two Thousand Days of Revolution. Paradigms of military revolutions. And also negative models, such as Chile: a tragic military revolution.

For the MFA, the Chilean military were committing crimes against their own people. They contrasted this with the Peruvian army, which had made “an original military revolution.” Another model was the revolution in Algeria. Admittedly, these models reflected more the spirit of the Fifth Division, where the officers closest to Colonel Vasco Gonçalves were based. But Cuba was also discussed. The visit to Cuba by Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho, who was photographed riding in a military car with Fidel Castro, caused a stir. Movimento, the Armed Forces’ newsletter, published a headline: “The MFA in Cuba”. In May 1974, the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (like their Cuban counterparts), linked to the Portuguese Communist Party, emerged in several industrial companies in Lisbon.

There were six governments during the “Carnation Revolution”: I, II, III, and IV had the participation of the PS (socialists), PCP (communists), PPD (popular democrats), and military; V was mainly supported by the army close to the PCP and VI had all the parties, but was dominated politically by the PS and allied military. The first revolutionary phase saw three coup attempts, the first on July 10, 1974, and September 28. The Third Provisional Government began in October 1974 and was marked by the rise of popular struggles. The last coup attempt in this series, on March 11, 1975, also failed.

Therefore, the three coup attempts failed. After the failed coup in March, the revolution deepened: At PCP rallies, its militants demanded, shouting as their leaders spoke, “out with the PPD,” in other words, a break with the policy of “national unity,” which had been their party’s policy since the beginning of the revolution. The revolution became politicized and showed a softer face after the period, symbolized by the carnations on the soldiers’ rifles.

On April 25, 1975, the revolution’s first anniversary, elections were held for the Constituent Assembly, with a 92% turnout. The PCP and PS, the main left-wing parties, won a combined (but separate) 51% of the total vote. The CDS, which proposed a return to the old corporatist regime, won just 7.65%. The elections reflected, albeit indirectly and certainly distortedly, the power relations in the country. The MFA felt its impact.

The restructuring of the correlation of forces in the MFA in September 1975 led to the creation of a group coming from an alliance between the Socialist Party, the “Group of Nine” and the right, a second group coming from the military left, very much in favor of third-world theories, which proclaimed the goal of “reaching socialism.” A third group comprised soldiers who favored the PCP (Portuguese Communist Party) and its policy of rebuilding the MFA, as well as a PS-PCP-MFA coalition.

Thus, the impasse caused by the civil disputes led the MFA to split into three main sectors. The one oriented towards popular power was linked to COPCON (Operational Command of the Continent) and headed by Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho, whose popularity grew due to the spread of his role in commanding the military operations of April 25; the second was linked to the government apparatus headed by the charismatic Colonel Vasco Gonçalves, the only senior officer committed to the Captains’ Movement before the seizure of power; the third was close to the socialists and to a moderate vision of the revolutionary process, and was allied to Major Melo Antunes, one of the authors of the MFA program.

In 1975, the divisions within the MFA were accentuated by the August publication of COPCON’s Autocritica Revolucionária, which defended popular power. The streets were filled with demonstrators. Workers’ committees began self-management experiments in some companies, several strikes were called, new occupations of houses in Lisbon, and demands for land reform. By the end of 1975, cooperative production units managed 25% of Portugal’s arable land. On January 13, 1975, the law on trade union uniqueness was passed, supported by the PCP, which recognized the Intersindical, dominated by the Communists, as the only legitimate workers’ union – the MFA looked to the PCP (which had doubled in size between June and September and had 100,000 members) as an instrument for maintaining order in the effervescent “world of work”, which was conducive to repressed wage demands.

The share of wages in national income jumped from 34.2% in the year immediately before the revolution to 68.7% at its end.[vii] The political parties sought to organize, direct, or control the autonomous initiatives of the working class: “There were various ways of having a force within this process, which is reflected in the councils set up in Lisbon (the Lisbon People’s Assembly/Commune) and Setúbal (the Struggle Committee) which articulate CTs and residents‘ committees and then soldiers’ committees. The most important will be the coordinator of CIL – Lisbon’s Industrial Belt. But also others more directly linked to the parties, such as the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs), linked to the PCP; the Revolutionary Councils of Workers, Soldiers and Sailors (linked to the PRP-BR). And there was also the First National Congress of Workers’ Committees (led by the MRPP, but also attended by the PRT).”[viii]

These were organizations with different conceptions: the Movement for the Reorganization of the Proletarian Party was Maoist, and the Revolutionary Workers’ Party was Trotskyist. The Portuguese Communist Party was more ostentatious in its defense of the political stability of the new order and acted to curb grassroots radicalism in defense of the “battle for production.”

On November 7 and 8, 1975, there was a meeting of the Workers’ Commissions of the Lisbon Industrial Belt, where the issue of workers’ control and the national coordination of workers’ commissions focused attention. The Fourth Government (dominated by the PCP) and the Council of the Revolution, after taking control of the banking sector and placing a sector that workers could control under state protection, adopted the strategy of a “battle for production”.

Sworn in as Prime Minister of the Fifth Provisional Government, Vasco Gonçalves was the target of growing protest. Two days later, Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho forbade him from visiting the military units integrated into COPCON and asked the general to “rest, rest, serenity, meditation and reading.” The country went up in flames with the political struggle and the escalation of violence against the headquarters of the PCP and far-left parties, especially in the north and center of the country. Until the November 25, 1975 crisis, there was a struggle between the policies of each of the three political-military groups.

In the same period, “between September and November 1975, there was a gradual construction of embryonic forms of coordination of workers‘ control at national level: exponential development of the strength of workers’ committees and the preponderance of political demands, against the state, within companies: construction of socialism, abolition of mercantile relations, abolition of class society, rejection of the call for national reconstruction, control of profits. This situation gave added impetus to the creation of embryonic forms of coordination of workers’ committees, which in Lisbon, where almost everything was decided by the high level of industrial concentration, came to fruition with force and great internal polemics.”[ix]

On November 25, there was a military confrontation between the left and other Armed Forces sectors. The victorious “colonels”, led by Lieutenant Colonel Ramalho Eanes, not only cleansed the Armed Forces of their radical left-wing elements, but also put the brakes on the careers of all the members of the MFA, even the moderate ones, and took over the command once and for all. November 25 began with an action by paratroopers. Whether Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho or COPCON officers gave the order is a mere detail.

It is known that the military right and the moderates of the MFA were prepared for an army takeover of the country and that they had an Operational Plan to do so. This plan involved the organized support of the Socialist Party and foreign powers (England and the United States). It could be argued that the left was also preparing. And accusations later surfaced that the PCP had dawned that day with nostalgia for the lost Revolution and had mobilized armed militants, only to be recalled in the evening. It would have been a retreat by the party in exchange for maintaining its legality. It’s hard to imagine such amateurishness on the part of the CC of the PCP. Still, even if the PCP was preparing a coup and Otelo was its military chief, there had been no unity on the left since the fall of the Fifth Government. A coup presupposes unity of command.

The idea that November 25 was a military action against radicals and moderates simultaneously remains valid. The attack was officially aimed at the extreme left and had the support of the moderates. However, the moderates realized on November 25 that the military action went beyond them. The new head of the Lisbon Military Region, Vasco Lourenço, and President Costa Gomes were upset and watched passively as the military and political command of the situation passed to the conservative Ramalho Eanes.

An anecdote paints this officer in full: at the May 1, 1977 parade in Lisbon, following his inauguration, he attended the celebration on the official stage. A woman nearby asked him why he remained so serious, not smiling, to which Eanes replied: “Because I’m not obliged to do so by the new Constitution, ma’am.” … In his speech to the Assembly of the Republic, Eanes paid tribute to the entire career of the Army and the police, warning: “Every day we witness [social] conflicts that, strictly speaking, should be classified as sabotage. There is an urgent need to regulate the right to strike.”[x] The sixth government, after November 25, was a kind of ‘government of national unity’, with a majority of MFA ministers in the cabinet. If April 25, 1974, began the dismantling of the state, November 25, 1975, and the Sixth Government started the dismantling of the revolution, albeit with a long way to go.

The colonels could not eliminate the MFA from the history of the Armed Forces, although they did eliminate it from their structure. April 25 became Freedom Day; the military was sent back to their barracks; the MFA and COPCON were abolished; and the Revolution became an “evolution” led by the recovered bourgeoisie. But not without popular protest. For Vasco Gonçalves, November 25th crowned a long process of change in the military correlation of forces and took on the appearance of a provocation and a counter-revolutionary coup.

It was the Socialist Party, led by Mário Soares, that played a key role in the reconstitution of the state, benefiting notably from subsidies from German social democracy and consolidating itself as the main electoral force after the failure of the coup insurrection of November 1975. In the Assembly of the Republic elections on April 25, 1976, the PSP won 35% of the votes, followed by 24% for the PPD, 15.9% for the CDS and 14.6% for the PCP. The far-left parties (MRPP, PCP-ML, PDC, and PRT) barely exceeded 1.5% of the electoral vote. For many, the revolution was over.

At the end of 1976, one of the authors of this text (the oldest, of course) was taking part in a large international Trotskyist meeting in Paris (he even chaired one of the sessions at a very young age),[xii] at which Portugal was a central point on the agenda. The report’s title was significant by a Portuguese militant: “Balance of the Portuguese Revolution”…

Was the April 1974 revolution a February Revolution not followed by an October Revolution? The battlefield of interpretations remains open. The Carnation Revolution was possible within the general framework of African decolonization, the indirect confrontation between the USSR and the USA, and the retreat of the USA in the face of the rise of class struggles since the 1960s (but especially because of its defeat in Vietnam). However, it was limited by the centuries-old structures of the Portuguese economy, its demographic distribution, agrarian arrangement, the ideological limits of its political elites, and the fact that it was led by an army incapable of transmuting itself into a decisively revolutionary body.

The MFA carried out a military coup followed by an urban insurrection in a country that still had a strong rural and Catholic influence. Its rapid ideological evolution occurred alongside that of the urban population (or a significant part of it). In this sense, it was not a vanguard. At the same time, the political parties didn’t have the legitimacy of arms, and April 25 was not enough to replace the MFA.[xiii]

As an integral part of the Armed Forces, the MFA could only become the leader of a radical, revolutionary process if it crossed the Rubicon and annihilated the rest of the Armed Forces. Being a minority fraction, it would have to use violence (or the threat of it) against people linked to members of the MFA by ties of comradeship forged in military schools/academies or in the colonial war, breaking with its own strictly military training; arm civilians and risk being submerged in a civil-military struggle and losing control of the state apparatus.

Without a revolutionary party, the MFA would have to fulfill a role that its rapid creation (in the short time) might have allowed it to do, but its slow formation (in the long time of the national armed forces) made impossible. As for the proletariat, the urban wage earners and the peasants, they were capable of unprecedented organizational initiatives – especially in the radicalization of the “hot summer” until the outcome of November 1975 –[xiv] without parallels in post-war Europe, but without being able to overcome the absence of a unified political orientation and a political leadership capable of carrying it out.

The social organisms of a revolutionary power were sketched out and even developed, without being able to present themselves as a political alternative for the country, which would have promoted the crumbling of the state’s armed corps. The main European revolution of the second post-war period was exhausted in its early stages without reaching its last potential consequences. After three years, when the revolution came to a political impasse, the Europe of NATO and the Cold War breathed a sigh of relief. But the scare had been enormous, even crossing the Atlantic and spreading worldwide.

*Lincoln Secco is a professor in the History Department at USP. Author, among other books, of História do PT (Ateliê). [https://amzn.to/3RTS2dB]

*Osvaldo Coggiola is a full professor in the History Department at USP. Author, among other books, of Teoria econômica marxista: uma introdução (Boitempo). [https://amzn.to/3tkGFRo]

Notes

[i] Francisco Carlos Palomanes Martinho. Authoritarian thought in the Portuguese Estado Novo: some interpretations. Locus. Revista de História, Juiz de Fora, vol. 13, nº 2, 2007.

[ii] Perry Anderson. Le Portugal et la fin de l’Ultra-Colonialisme. Paris, François Maspéro, 1963.

[iii] Ronald Chilcote. The Portuguese Revolution of April 25, 1974. Annotated bibliography on the antecedents and aftermath. Coimbra, University – April 25 Documentation Center, 1987.

[iv] Paulo Moura. Otelo: the Revolutionary. Lisbon, Dom Quixote, 2012.

[v] Charles Downs. Revolution at Grassroots. Community organizations in the Portuguese Revolution. New York, State University of New York, 1989.

[vi] Apud 25 Avril. La dictature fasciste s’effondre à Lisbonne, problèmes de la révoluton portuguaise. Paris, SELIO, 1974.

[vii] Lincoln Secco. The Carnation Revolution. Economies, spaces, and awareness. São Paulo, Ateliê, 2024.

[viii] Raquel Varela, António Simões do Paço and Joana Alcântara. Workers’ control in the Portuguese Revolution 1974-1975. Marx and Marxism, vol. 2, no. 2, São Paulo, January-July 2014.

[ix] Raquel Varela, António Simões do Paço and Joana Alcântara. Op. cit.

[x] Sérgio Reis. Portugal: the moment of the situation. La Vérité no. 581, Paris, April 1978.

[xi] Vasco Gonçalves. A General in the Revolution. Interview with Maria Manuela Cruzeiro. Lisbon, Editorial Notícias, 2002.

[xii] The Committee of Organization for the Reconstruction of the Fourth International (CORQI) had recruited the socialist deputies Carmelinda Pereira and Ayres Rodrigues to its ranks. The Unified Secretariat (SU) of the Fourth International was also present.

[xiii] Maria I. Rezola. 25 de Abril. Myths of a revolution. Lisbon, A Esfera dos Livros, 2007.

[xiv] Miguel Ángel Pérez Suárez. Down with Capitalist Exploitation! Workers’ Committees and Workers’ Struggle in the Portuguese Revolution (1974-1975). São Paulo, Lutas Anticapital, 2023.

Full essay in Portuguese

We thank the Luso-American Education Foundation for sponsoring PBBI-Fresno State and establishing this cultural platform as a community outreach program from PBBI-Fresnp State.