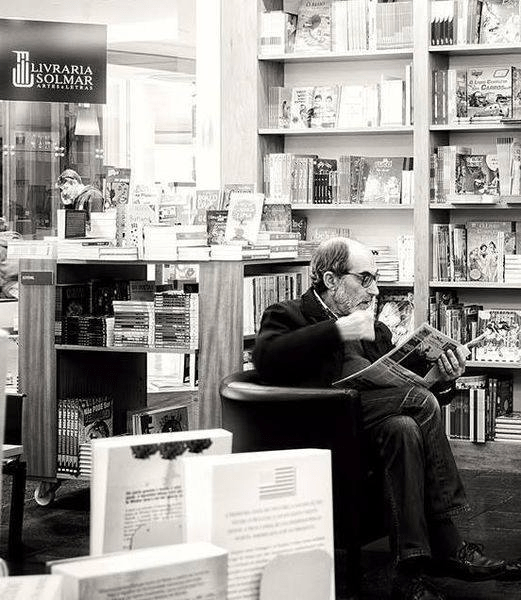

The writer Urbano Bettencourt recently launched the 3rd edition of his book “Santo Amaro sobre o Mar” at Livraria SolMar in Ponta Delgada. The great novelty is that it is a bilingual version with an English translation by Professor Rosa Neves Simas. This book presents a brief tour of the parish of Santo Amaro on the north coast of the island of Pico. It revisits some names and events from its history, such as shipbuilding and its external connections, particularly in California.

Correio dos Açores – The 3rd edition of your book “Santo Amaro sobre o mar” will be presented this week in Ponta Delgada. What story do you tell in this book?

Urbano Bettencourt (writer, poet) – First of all, it’s important to say that this book came about at the “request” of my friend Alberto Péssimo, an artist born on the island of Mozambique and living in Porto, where he works.

In 2002, he was on vacation in Santo Amaro do Pico, made a series of drawings (one about Prainha, the parish next door, and also included in the book), and asked me for a text for the drawings. I ended up constructing a series of individual stories that relate to the historical reality of Santo Amaro: personalities and events; as a whole, I think they make up a profile of the parish at a specific time. But it’s a book in which the physical author doesn’t fail to get involved, especially in the last of the texts.

The great novelty of this edition is that it is bilingual, with an English translation by my friend Professor Rosa Neves Simas, a native of Santo Amaro who was also in the book’s presentation.

This book’s narrative focuses on the art of shipbuilding and preserving heritage and collective memories. In an age when traditions are being forgotten or readapted, how can books help revive them and interest young people?

Shipbuilding is integral to my narrative because it was one of the parish’s core activities, with direct and indirect economic repercussions far beyond its territorial limits, even outside the island. An activity, it should be added, with American connections, thanks to the young Manuel Inácio Nunes, who left Santo Amaro at a very young age and, with his brother António, built his flagship shipyards in Sausalito (California) while also supporting shipbuilding in Santo Amaro.

The remaining heritage requires an attitude on the part of the public authorities to preserve and boost it as a cultural and economic asset. It also represents a factor of local identity when the tourist invasion erodes the memory and individuality of people and places.

Creating a shipbuilding museum in Santo Amaro (a branch of the Pico Museum, as you like) is not a favor to anyone, much less a quirk: it is an act of cultural justice and respect for a community and its history.

The book’s presentation will be an opportunity to discuss these things, so I invited my friend, Amaro de Matos, also from Santamar. With whom I shared a childhood, he has dedicated much of his time to researching and recording the history of Santamar shipbuilding—he is the right person to talk about it and its authors.

Many consider him one of the most outstanding intellectuals in Azorean culture. Is our literary culture valued by the Azoreans and by the competent bodies of the Region?

The initial statement is not my responsibility, although I can recognize, with as much distance as possible, what I have been doing in the area where I am involved. However, there are other active players in cultural sectors other than mine. And I think these things shouldn’t be seen in terms of a championship or a league but complementarity.

In 2026, Ponta Delgada will be the Portuguese Capital of Culture. In your opinion, how important is this nomination for Azorean culture and literature?

I don’t have enough information to say what will or won’t happen. Even so, I think it’s an opportunity to promote activities in various fields, provide training for agents from multiple cultural institutions, create the possibility of intervention for others, and promote exchanges in a decentralized and uncomplicated way. But it’s best to wait and see (and believe).

Are the works of Azorean writers being appropriately made known to students in our education system?

I know of cases in which, fortunately, this is happening, mainly due to the dedication and commitment of some teachers who breathe and survive through pedagogical bureaucracies and the like. But I don’t know the actual extent of this process in the region.

Are new technologies and Artificial Intelligence facilitating or, on the contrary, destroying intellectual reasoning? Can you explain?

The new technologies have never replaced me in the moment or in the act of thinking and reflecting; I recognize their usefulness as working tools, capable of quickly providing me with materials and information that I am responsible for selecting and organizing.

What message would you like to send to those who should pay more attention to the Portuguese language?

Sloppiness in language use is as symptomatic as in other areas (clothing, hygiene, etc.).

Any projects in the creative process?

I have a narrative in a very embryonic process, almost just a project still being organized. But the next few months will be spent away from that, preparing some interventions I’ll be doing in the Canaries throughout 2025: island literatures and cultures, always.

Do you have any message or advice for aspiring young writers?

There’s no writing without reading and patience.

Neuza Almeida is a journalist for the newspaper Correio dos Açores – Natalino Vivieiros, director.

Translated to English as a community outreach program from the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI) and the Modern and Classical Languages and Literatures Department (MCLL) as part of Bruma Publication and ADMA (Azores-Diaspora Media Alliance) at California State University, Fresno, PBBI thanks the Luso-American Education Foundation for sponsoring FILAMENTOS.