A weekly segment of PBBI-FresnoS tate today with a contemporary essay by a poet and a friend.

Everything Fine? Is it really okay? By Aníbal C. Pires

The presentation of a book at the Letras Lavadas bookstore in Ponta Delgada. The timing wasn’t perfect: in the middle of a summer Saturday, there wasn’t expected to be much of an audience, and there wasn’t. But even so, a few people were always interested in attending the presentation. But even so, a few people were still interested in attending the presentation of Thomas Fischer’s Entre Cravos e Cardos (editions 70, 2024). There had been some publicity in the national and regional media. The subject was related to the experience of a German citizen who had come after the April Revolution, who decided to live in Portugal in 1983, and who acquired Portuguese nationality a few years ago; these facts combined with some natural curiosity about the “other’s” view of us, even if that “other” is already one of our own, is always enticing and often takes on a didactic character, in addition to the fact that at times it can make us smile when we identify with the description, or perhaps frown when the assessments are not to our liking, which is not the case as you will see if you read the book.

Thomas Fischer is German by birth but spent part of his childhood in England, where he began his elementary education. After returning to Germany, he completed his secondary education in the Bremen area and then went on to higher education (journalism, economics, and sociology) in Cologne. He was German in England and “English” in Germany. Despite decades of residence and the acquisition of nationality in Portugal, he remains a “foreigner.”

The young people of Thomas’s generation lived through a time of great utopias but also of great achievements and social and political changes that shaped and mobilized them.

The events, concerns, and lifestyles of young people in the late 60s and early 70s. Woodstock, the sexual revolution, the government of popular unity in Chile, but also its tragic end, the Vietnam war, the Cuban revolution, some artificially created disillusionment with the paths taken by the socialist countries of the East, the April revolution in Portugal and the fascination it exerted on many young and not so young European citizens, but also those from South and North America, and other more distant territories.

The characteristics of the April Revolution and the transformations that took place during the revolutionary period attracted many young women and men to our country, from the most diverse geographical backgrounds and with different objectives. Each wanted to feel the pulse of an unusual military coup d’état that, instead of establishing a dictatorship, ended one and established a democratic regime.

The social and economic transformations of the April Revolution attracted hundreds, perhaps thousands, of young people linked to the political and social struggles in their countries of origin. Agrarian reform, popular democracy, and self-government mobilized these young people, who didn’t come just to feel but to participate actively. Some had the genuine attitude of integrating themselves into the revolutionary process, others not so much. But that’s another matter.

It was in this context that Thomas Fischer arrived in Portugal in 1975. Like him, many other foreigners had passed through Portugal: musicians, journalists, intellectuals, political leaders and trade unionists, some of whom are well known, such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Alain Touraine, Jean-François Revel, Jean Daniel, François Mitterrand, Gaston Deferre, Lionel Jospin, Georges Marchais, Alain Krivine, Heinrich Böll, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Robert Kramer, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Like many foreigners who came to feel the pulse of the April Revolution, Thomas Fischer returned to his ancestral roots. But Thomas Fischer came, he saw, he liked, came back in 1983, and stayed here. He knows Portugal as few Portuguese do. He maintains a solid connection to the Azores, which he visited for the first time in 1983, which is, curiously enough, the year I settled here. This book tells us about his many journeys through Portugal, about the events that have marked our contemporary history, but also about “being Portuguese,” its paradoxes, and even some “mysteries” yet to be unraveled, such as being able to live on salaries that shame us and continue to push many of our fellow citizens into emigration and ever deeper into poverty.

At the beginning of the presentation, after thanking those present, the author, and Letras Lavadas, I gave Thomas a test using a recurring question in the book to see if the author was already imbued with the genuine Portuguese spirit.

Hello, Thomas! Is everything all right?” To which Thomas replied: Yes, everything is fine. The answer was as expected. Thomas had already appropriated a characteristic that, while not everything, says a lot about being Portuguese. As we know, this question always has the same answer, even if everything is wrong. Rarely do we get an answer to the question “How are you?” other than “Everything’s fine.” We can carry pain, sadness, anxiety, anguish, but when asked by someone who isn’t part of our circle of family or close friends, the answer is always “everything’s fine”. In his book Entre Cravos e Cardos, Thomas explores this and other facets that, for better or worse, characterize us.

The book’s cover is an excellent summary of the content, the graphics, and particularly the stylization of the two flowers that give the book its title and between which dreams have been built and faded.

The carnation is a flower that symbolizes respect, love, and passion. Carnations are part of the Portuguese imaginary, as there are few Portuguese houses where there isn’t “a carnation blooming in an attic,” as a well-known fado sung by Amália Rodrigues puts it, but also in a vase by the window, or even in the small gardens of famous houses. In addition to their varied colors, they exude a subtle and pleasant aroma, contributing to their popularity. In Portugal, with Celeste Caeiro’s gesture on the morning of April 25, the red carnation gained a new and exponential symbolism. It gave its name to the revolution that is often referred to as the Carnation Revolution.

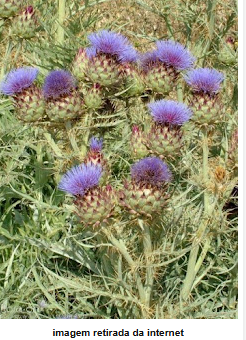

The thistle is a wildflower that contrasts with the delicacy of carnations. It is thorny, withstands heat well, and thrives in sandy (poor) soils. While the thistle flower is unpleasant to touch because of its prickly leaves, it is also a beneficial and decorative plant that blooms in summer in a profusion of beautiful pink-purple flowers. Its primary use, among others, is to curdle milk to make the delicious cheeses of Serpa, Azeitão, Beira Baixa, and Serra da Estrela, among others. Thistles have also always been used in gastronomy and, more recently, in medicine.

Thomas Fischer’s book could be called the book Between Utopia and Reality. The dreams were born with the beautiful red carnations of April and a people who continue to survive in a country that has never valued or mobilized its citizens. Life for most Portuguese is, like the thistles, complex and thorny. Fifty years after the Carnation Revolution, the Portuguese people still, like the thistles, “surviving” in inhospitable environments without knowing how. Thistles, like the Portuguese, have an underused intrinsic potential, which is now beginning to be adequately studied and valued in the case of thistles. The book’s title and cover are a happy metaphor.

Ponta Delgada, October 29, 2024

Aníbal C. Pires, In Diário Insular, October 30, 2024

Translated by Diniz Borges