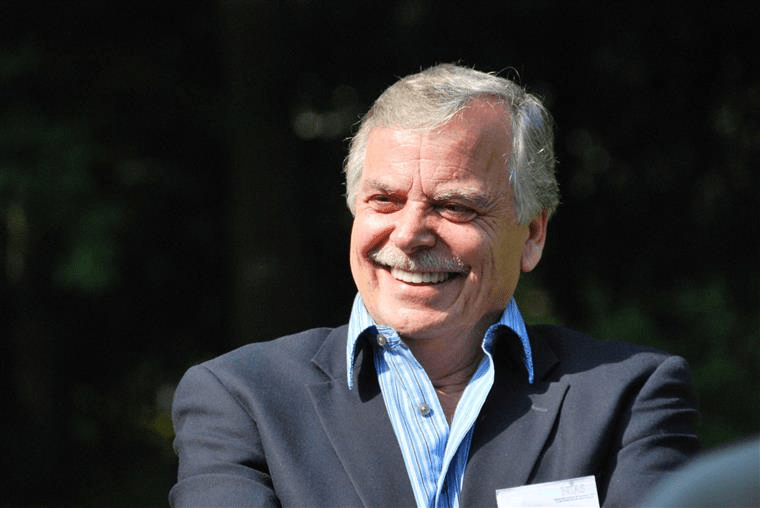

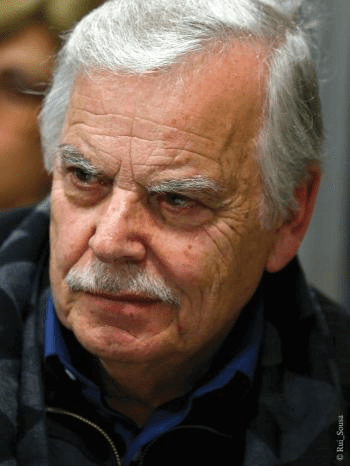

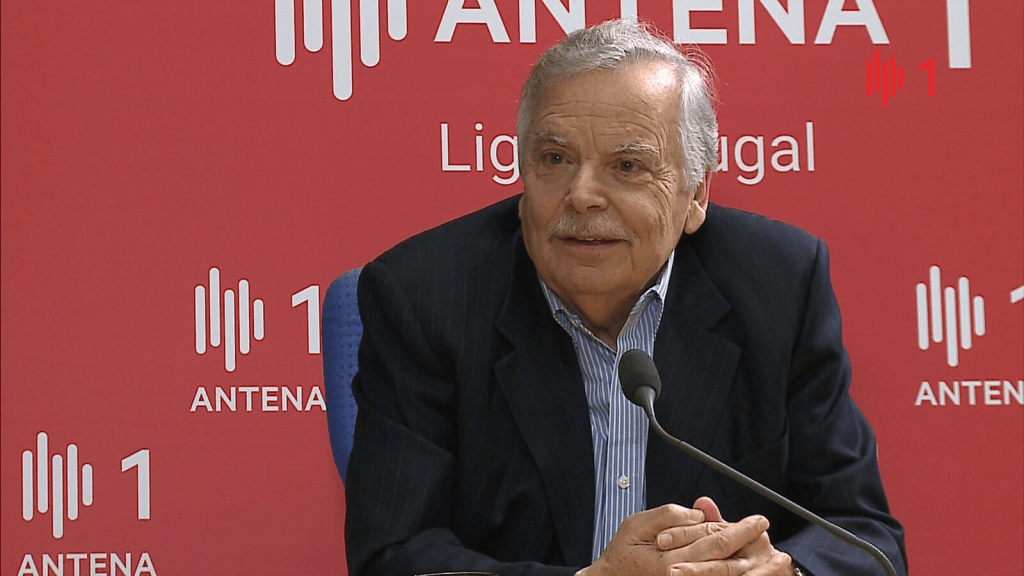

Onésimo Teotónio Almeida presented ‘Diálogos Lusitanos’ (Lusitanian Dialogues), his latest book, in Ponta Delgada, where he dialogues with 20th-century Portuguese authors such as Vergílio Ferreira, José Saramago, Eduardo Lourenço, Natália Correia, José Enes, and Jorge de Sena. Here, as with all his work, the reflections of the author of ‘O Século dos Prodígios’ are not limited to the text or the literary work itself but include ethics and aesthetics as inseparable dimensions – as he says: “The worldviews of people and nations, which encompass the fundamental values by which people and collectivities are governed, have always been the central issue of my studies and writings.” Except for Fernando Pessoa, Onésimo Teotónio Almeida has met all the figures featured in the dialogues in this book, many of whom are his long-time friends. However, for all that he couldn’t summarize in this interview, the author presents us with a roadmap to find caricatured moments, reflections, and stories, such as the one featuring Natália Correia in ‘Quando os Bobos Uivam.’ In addition, the professor at Brown University in the USA, who for more than 50 years has dedicated himself to breaking down the “thick barriers” between the English-speaking and Portuguese-speaking worlds, says that he still hopes to foster a more open dialogue about Portuguese culture in a country where “there are still no great intellectual debates.”

Correio dos Açores – ‘Diálogos Lusitanos’ explores the works and the ethical and aesthetic values of various figures in Portuguese culture. What motivated you to focus on these themes rather than just the literary dimension? Do you think they are inseparable?

Onésimo Teotónio Almeida (Writer, Philosopher, University Professor) – I’ve been doing this all my professional life. My doctoral thesis in Philosophy was on the question of ideology. The worldviews of people and nations, which encompass the fundamental values by which people and collectivities are governed, have always been the central issue of my studies and writings. I have dedicated myself to them from a theoretical point of view, but I have also applied the problem of worldviews to the Portuguese and Azorean cases. For example, in the same year I defended my thesis (1980), I published an extended essay entitled ‘A Profile of the Azorean.’ The courses I taught at Brown all centered around this theme. Even when I taught a course on Azorean literature, I used literature to help students get to the bottom of the Azorean culture.

In a philosophy course I taught at Brown for 42 years, we studied Nietzsche, Marx, Max Weber, and other modern thinkers. The big question was their worldviews and the ethical values behind them. Aesthetics always reflects ethical values, hence the inseparability between the two fields. All my writings, even my short stories, chronicles, and theater, reflect these theoretical interests that are central to my personal and existential concerns. Anyone who reads my books in this light will recognize what I’ve just said.

Your book is structured as conversations with key figures in 20th-century Portuguese culture. What led you to choose this formula? What do you see as the advantage of using this approach?

It’s not really a choice, at least not consciously. I’m constantly asked to contribute articles to magazines and collective books, or to give talks here and there. Many of these invitations are to mark ephemeris, such as the centenary of a figure’s birth or death. Natália Correia, Eduardo Lourenço, Fernando Pessoa, José Enes, Vergílio Ferreira, José Saramago, for example. I write from the point of view of my theoretical interests, so I write about the worldview and underlying values of their personalities and lives. I’m currently finishing a book on the question of modernity. Still, in the meantime, I’d accumulated a large body of writing in response to various invitations, and I thought this would make for a coherent volume. In 2015, I published another similar book – ‘Despenteando Parágrafos’ – with Quetzal. I’ve even published a book in this genre about Azorean authors – ‘Minima Azorica’. ‘My world is of this realm’ (Companhia das Ilhas, 2014).

Can you imagine the Azores without these figures from its past?

No. “My” Azores wouldn’t be the same without figures like Antero de Quental, Vitorino Nemésio, José Enes, and so many others. They would be much poorer, and we wouldn’t have deepened their collective consciousness so much, nor would they know the dominant forces of their history so well. Many Azoreans would not have been inspired and encouraged by these tutelary figures.

You personally lived with some of the authors mentioned in the book. What was it like being close to such distinguished figures in Portuguese literature and culture?

It was a very enriching experience. You always learn a lot when you meet people who know more than you. Since I was young, I’ve worked with great teachers who have become my mentors. José Enes was fundamental in my life. My contact with him began when I was 13. He wasn’t my teacher, but I was head of course, and he was Prefect of Studies. We had to interact, and he started lending and recommending books to me. But that was just the beginning. He taught me a lot all my life, and that can’t be summed up in an interview. I’ve already written a lot about him. The last time was a few days ago at a colloquium in Lisbon, commemorating the centenary of his birth, and it hasn’t been published yet.

I was a personal friend of Eduardo Lourenço and lived with him for four decades. I even had him for a few months at Brown as a guest lecturer. I was also friends with Vergílio Ferreira. I only had him at Brown for a few days, but I met him regularly whenever I went to Lisbon, and we corresponded. His diary, Conta-Corrente, tells us about it. I met Natália Correia in 1978 when I invited her to Brown, but we had many more contacts until she died in 1993. José Saramago contacted me late in 1995, expressing his desire to go to the USA when he was not yet a Nobel Prize winner. I organized a tour for him at his request, but he had to postpone it until the following year. From 1996 onwards, we were in touch many times, we corresponded and I even collaborated with him on some projects. One of them was incomplete because he had passed away in the meantime. He asked me to organize a session on Azorean literature at the Casa do Alentejo in Lisbon after I had organized one on José Rodrigues Miguéis, whom he admired very much (I had the correspondence between the two of us published). His aim was to draw Lisboners’ attention to the great literary tradition of the Azores.

My contact with Jorge de Sena and José Rodrigues Miguéis was short-lived because they died a few years after I arrived in the USA. But I still had Jorge de Sena at a colloquium at Brown, and José Rodrigues Miguéis’ estate is at Brown, given to me by his widow. In other words, not only did I have contact with these authors, but I also read the books they were publishing.

In the case of Fernando Pessoa, I was born eleven years after his death, so I couldn’t have known him. However, I wrote a book about him, ‘Pessoa, Portugal and the Future.’ In addition, I’m part of the management team of the only magazine about the poet – ‘Pessoa Plural’ – published by Brown. But this book of mine has other texts that aren’t about figures. It includes, for example, my speech on June 10, 2018, read at the ceremony in Ponta Delgada at the invitation of President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, and it also includes, among many others, a text on April 25, presented at the Lisbon Academy of Sciences.

Can you share a memory or a funny episode you had with some of these authors?

Any of them would take up too much space as I would have to explain the contexts. However, interested readers will be able to find a long story involving Natália Correia, which I told in a seventy-page narrative in my book ‘Quando os Bobos Uivam’ (2013). Another series of episodes involving António Lobo Antunes, among other writers, occurred in Ponta Delgada in 1987. I have a dossier of almost a hundred pages about it. It’s impossible to summarize it here. However, I will never publish it because I prefer to tell entertaining stories without insulting people. That’s why I stick strictly to the facts when I tell some less edifying ones. Many were caused by misunderstandings, ignorance of cultural contexts, or life circumstances that affect people’s decisions through no fault of their own. Things that happen to anyone, including me. But I have amusing stories with Eduardo Lourenço, Vergílio Ferreira, Jorge de Sena, Manuel Alegre, and many others (and I’m only mentioning Portuguese) in books of chronicles such as ‘Que Nome É esse, ó Nézimo?’ (1994), ‘Viagens na Minha Era’ (2001) and ‘Livro-me do Desassossego’ (2008).

After ‘Século dos Prodígios,’ did you feel any changes in your creative process when writing ‘Diálogos Lusitanos’? What were the main challenges or surprises during the writing of this book?

Século dos Prodígios is a book that combines essays written over 38 years. I wrote hundreds of other essays, articles, chronicles, and short stories during those same years. Some of the writings in ‘Diálogos Lusitanos’ predate ‘O Século dos Prodígios’, such as the essay on José Enes, or the one on humor in Portuguese literature. However, most of them are later. But I’ll repeat what I’ve already told you: this book brings together various speeches I’ve made in recent years in Portugal, the United States, France, and Brazil. They reflect the interests I’ve had for half a century. However, my writing process has been the same throughout. The difference lies in the literary genres used. The rules are one when I write short stories or chronicles; when I write essays, they are another. However, the underlying problem remains consistent.

In the preface, you mention your desire to foster a more open dialogue about Portuguese culture. You believe that this book can contribute to that expansion. How do you see this “dialog” evolving over the years?

I hope so, but that doesn’t mean I’ll succeed. There aren’t ample intellectual dialogues in Portugal. Everyone monologues in their own corner. When someone challenges someone else’s writing to have a conversation in disagreement, it’s seen as a criticism or an attack. In the past, the famous public polemics would break out, and the one who hit the hardest would win. We don’t have this tradition of open, public dialog. But that doesn’t stop me from trying, even though experience proves otherwise. I make my contribution, and the rest is not up to me. As with everything in life, when you do what you can, you’re not obliged to do more.

You believe that precise language is essential for good communication. How do you react to the more formal and ornate academic writing trend?

I’ve advocated clarity of language since I was a student at the Angra Seminary. As a student at the university in Lisbon, I wrote in newspapers against the stilted and presumptuous writing that dominated the press at the time. However, the technique of stiltedness and/or hermeticism was partly motivated by fear of censorship. My entire philosophical education in the USA was geared towards exploring the great questions of Western thought in language that could be understood by the people involved in the conversation. I’m not against formal language. Language styles must adapt to different levels of formality. What I am against is unnecessarily complex writing, the intention of which is to hide the fact that the author doesn’t have much to say but has to give the opposite impression.

How do you see the reception of Portuguese literature and culture abroad, especially in the United States? Do you think it is properly appreciated, or is there still some way to go?

One of the texts in this book is precisely about that, and I can’t summarize it here in half a dozen words. I’ll just say that for over fifty years, I’ve tried to break down thick barriers in the English-speaking world that are highly resistant to anything that has to do with the Portuguese-speaking world. I wasn’t the only one engaged in this fight, but I did my bit. It took time to have an effect, but the situation has improved considerably over the last two decades, notably since the Nobel Prize was awarded to Saramago. For example, getting Fernando Pessoa into the English-speaking world was challenging. The individual efforts of various figures gradually succeeded in breaking through.

Today, the prominent New Directions publishing house in New York is publishing several translations of Pessoa. Many of Saramago’s works have been translated into English. But I tell you all this in the book. What I don’t tell you is that, even in retirement, I’m still involved in this field: I’m co-directing a series of Azorean literary works in translation at Tagus Press, at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, at the Dilúvio publishing house in Lisbon, with the help of Leonor, my wife, we’re collaborating on publishing translations of the great Portuguese poets. Translations into English, Spanish, Italian, French, and Japanese are already being circulated. I’m also co-directing a collection of works on Lusophone themes at Liverpool University Press in the UK. Here, decades ago, all this would have been unthinkable.

Daniela Canha is a journalist for Correio dos Açores - Natalino Viveiros, director