STORIES OF THE TIME

THE OTHER LADY

Of course, the Estado Novo looked after us all. But buying shoes and paying enough to buy them was an abuse, I later learned, a luxury that not everyone was entitled to.

JOSÉ FANHA*

I’ve ALREADY TALKED ABOUT the Alcâncara neighborhood, where, from the late 1950s to the mid-1960s, I spent a large part of my childhood with my grandmother Bertha, whose name was a TH- Tê Agá.

I later learned that, in World War I, the Germans invented a very powerful cannon with which they were firmly convinced that they would win the war. They named this cannon Bertha with TH-Tê Agá.

The truth is that cannon or no cannon, they lost the First World War, and I always thought it was an excellent idea not to mess with my grandmother’s name.

But let’s go back to Alcântara. The house where I lived with her was near Largo do Calvário, in a complex of tiny houses for widows of of army officers who had died in Africa, such as my grandfather Jaime, who had taken part in the battle of La Lys in World War I and died of an infection in the city of Beira in Mozambique at the end of the 30s.

When I lived there later, it was a working-class neighborhood with many workshops and large factories, a blue neighborhood—the most dignified blue I’ve ever known. I would walk around with my grandmother and look at Lisbon, so different from the one I had been born in, around Arco do Cego, Praça de Londres, and Alameda Afonso Henriques. Between the exit and entry sirens, the workers ate their lunch in the street, leaning against the wall with lunchboxes brought from home and bottles of carrascão.

Various vendors and trouserless women passed by. They and many boys, also barefoot, went to school. And I’d see those thick, dark feet running, jumping, kicking balls of cloth, banging on pointy stones, and opening gaps that would have to be closed by who knows when.

But why don’t they want to wear shoes?

Yes, they do! They told me. It was their parents who couldn’t afford them.

Of course, the Estado Novo was looking after us all. But buying shoes and paying enough to buy them was an abuse, I later learned, a luxury that not everyone was entitled to.

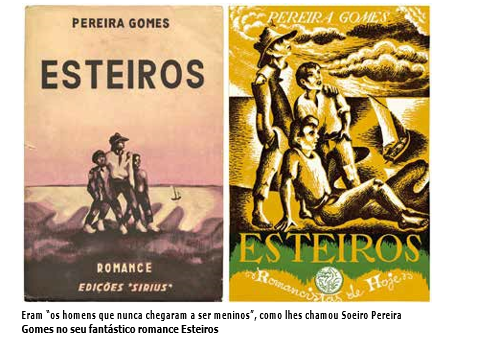

So, although it was a bit providential, the Estado Novo was no fool either and quickly solved the problem by creating a stiff fine for anyone who insisted on walking barefoot in the city. So, to avoid the fine, poor parents forced themselves to buy shoes or sneakers for every two children. If the police caught them, they’d say they’d forgotten the other shoe at home. It was the way out for those people with thick, calloused feet. They were “the men who never got to be boys.” As Soeiro Pereira Gomes called them in his fantastic novel Esteiros.

* Poet, A25A member

in Referencial Number 148-Edition January-March of 2023.

Translated by Diniz Borges for PBBI-Fresno State.

We thank the Luso-American Education Foundation for their support.