Doctoral student Pedro Cordeiro Ponte strongly criticizes the various government cycles concerning the situation of the Azorean historical figure’s estate. “Natália Correia died 31 years ago. The Regional Government has never fulfilled its duties in the face of her and her husband’s will to put the estate on display.”

Correio dos Açores —You are writing a doctoral thesis on Natália Correia’s political thought. Can you explain this idea and the purpose of the thesis?

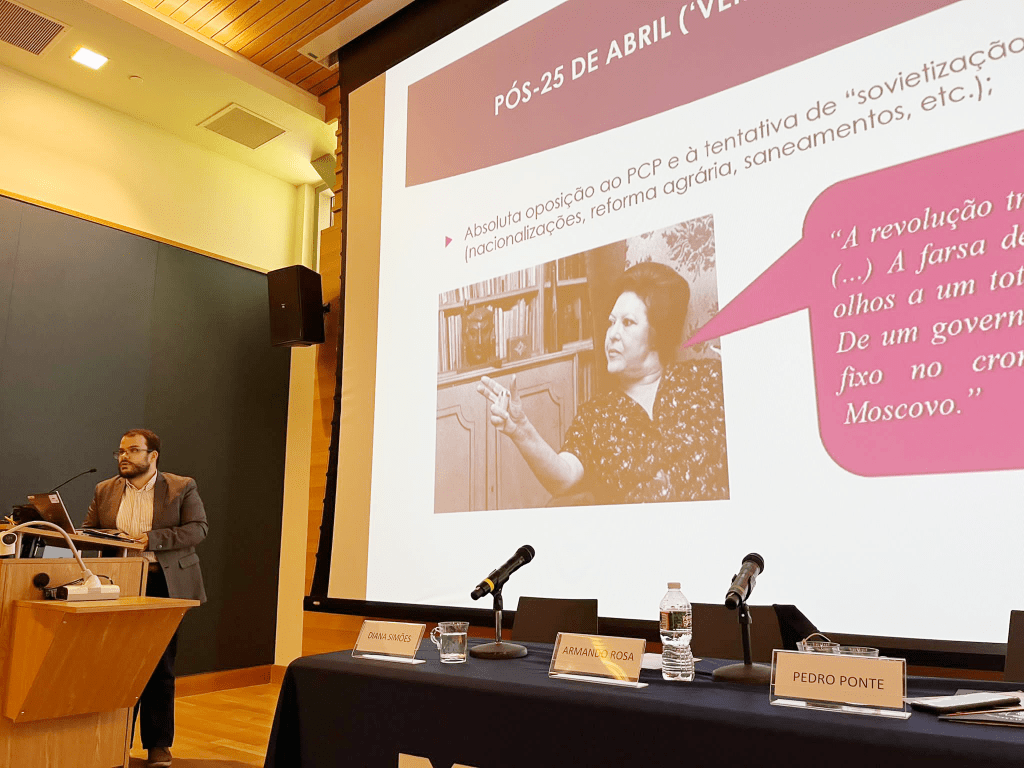

Pedro Cordeiro Ponte (researcher and teacher) – Of course. My thesis concerns Natália Correia’s political thought, especially in the post-25 April period. As an independent, she circulated about party affiliation and benches in the Assembly of the Republic. And there was a lot of talk, and sometimes there still is, especially during the centenary, that she was something of an “ideological weather vane”. Because it seemed that, as she had little stable financial income, so to speak, especially after the death of her husband, she moved around as she was invited and not out of firm convictions. When I took part in a congress in the United States on the theme of her centenary, I realized that people have to investigate and get ahead because she has an estate in Ponta Delgada that has a beginning but not yet an end.

For me, she wasn’t precisely a weather vane. She was always very consistent with her ideals during the Salazar period. The thing is, she wasn’t disciplined in party terms. She had substantial center-left values, which ended up not happening to the PSD with the death of Sá Carneiro, who was the one who invited her and got her to join. Then, as we know, the party became center-right, stronger with Cavaco Silva.

She was deeply anti-communist, even before April 25, and any drift led her to distance herself. In addition, she was a supporter of everything to do with culture or women’s rights, for example, at the time, the abortion controversy or a certain lobby in defense of culture, which even had the support of Mário Soares. When she saw that there were factors in her parties, such as Cavaco Silva’s PPD or Ramalho Eanes’ PRD, that were contrary to her beliefs, she would throw in the towel and disaffiliate, resign, or move away. It also had to do with her persona, her posture, and her speech. She could seem fickle and have incoherent speech, but the truth is, from what I’ve seen and read, that is just the draft of the draft. For me, she was always coherent. She was always utopian and ideological, but she never stopped being consistent with what she wanted. She was also anti-European in the sense that we are today, with the European Union as it is. In a way, she herself prophesied economic and financial issues rather than solidarity or the social pillar. She abhorred everything that was federalism and that focused on an economic-financial aspect.

In your view, and in this case, looking at history, do you think art is often seen without its political side?

In my opinion, it was deeply forgotten. I had colleagues and Portuguese teachers who didn’t know Natália Correia, not even by name; that’s a fact. Her lyrical work is probably better known, but not much. Her dramatic work is completely forgotten, and she was an absolute pioneer in theater.

What remains of her are the more theatrical situations of her persona, both in the Assembly of the Republic and in particular situations. I don’t think her work has made much of a mark, and her thinking much less so. I think she’s been forgotten in all the circuits; she’s much more valued in Lisbon.

In the year of the centenary, I noticed that there were a lot of events all over the country, in regions and areas that clearly have no connection with her. And in the Azores, at the start of the centenary, at least at the University of the Azores, where I graduated, it was tough to organize anything. Even the start of the celebrations by the Ponta Delgada City Council was a bit halting, and I didn’t even think there would be any celebrations.

In political terms, the only thing we know about Natália Correia is that she was a PPD activist during Sá Carneiro’s time and the abortion controversy, in which she wrote a poem to a CDS MP about “Morgado’s coitus.”

There’s not much substance to Natália Correia anywhere. I’ve also heard comments from people of letters in the Azores saying that “she lived in Lisbon all her life.” So, as soon as you use the parties to make a literary study, culturally, you don’t get very far. It may be a slightly polemical opinion, but that’s what I think.

Returning to Natália Correia’s estate, do you think there isn’t much historical research?

In terms of her estate, I’m suspicious. Poet and researcher Ângela Almeida has done an extraordinary job with it. We must bear in mind that the collection is huge, there are dozens and dozens of boxes, it’s not a piece of cake and nothing can be done overnight.

Natália Correia died 31 years ago. The Regional Government has never fulfilled its obligations under her and her husband’s will to put her estate on display. I’m not just talking about her documentary estate, but everything from Lisbon, such as clothes and art. It’s all been boxed up in the Carlos Machado Museum for decades. I’ve never understood why. I’m afraid I’m being unfair, and maybe there are reasons for it, but it’s always been hidden away, and I’m not sure in what condition. It’s a very murky subject. I’ve never understood it. The people I know who study Natália Correia and ask for access to her estate are not Azorean. We had a phenomenal biography by Filipa Martins, but it had to be a Lisbon initiative.

The collection is extremely well organized, the problem is that nobody is interested. It’s a bottomless pit. In the Azores, there’s some kind of impasse, but a decades-long impasse in relation to the non-literary collection.

The Museum was closed for decades during the Socialist government, then it reopened and it doesn’t seem to have changed hardly at all, and then they held an exhibition last year, on the centenary, with her clothes, which were put away again. The truth is that it is lost when the estate is not treated, classified, or inventoried. This isn’t partisan or political criticism; this has been going on for several government cycles. She donated her estate to the region during her lifetime, and I would like the area to value it; it was where she was born. I’d like the estate to be displayed, not boxed up.

José Henriques Andrade is a journalist for Correio dos Açores-Natalino Viveiros, director

Translated to English as a community outreach program from the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI) and the Modern and Classical Languages and Literatures Department (MCLL) as part of Bruma Publication and ADMA (Azores-Diaspora Media Alliance) at California State University, Fresno, PBBI thanks the Luso-American Education Foundation for sponsoring FILAMENTOS.