(Note from Filamentos: We are honored to feature this extensive interview with José Lourenço, director of the newspaper Diário Insular. We urge you to read it for those who want to know a bit more about the Azorean press. The Azorean newspapers have a long history in the archipelago.)

How did Diário Insular come about?

Diário Insular was founded in 1946 and was owned by Sociedade Terceirense de Publicidade, Lda, in the middle of the post-war period. At the time, the Church owned only one other newspaper in Angra do Heroísmo, União. The Diário Insular (DI) was an alternative, a civic movement driven by new ideas. The newspaper was founded by a group of intellectuals from the island, led entrepreneurially by the grandfather of the Brasil family, to which I belong. The newspaper evolved and went through some remarkable phases, one of which was the earthquake of 1980, which partially destroyed the premises in the city center in Rua dos Minhas Terras. By then, the company had been reduced to three partners. From the 1980s onwards, it became the sole property of the Brasil Peixoto family. And so it has survived as a family business to this day.

Does it have a regional expression?

I’d even say it’s more of a local expression, although the regional is at the center. What interests us is what happens on Terceira Island in particular. Then, what happens in the Central Group, particularly on the islands without newspapers, such as São Jorge, Graciosa, and even Pico. And then, of course, everything that happens in the Azores. Anyone looking at Diário Insular, which currently has a 24-page daily edition, will see that we invariably have no national or international news. Other media do this much better than we do, and we prefer not to replicate this news and to devote ourselves, heart and soul, to what happens between us and to the political and economic balance between the islands. The Azores have this particularity: nine islands, nine worlds, and nine idiosyncrasies. We are all Azoreans, but we are all pushing for the development of our land. The islands are different in size, population, and growth. That’s why the Azores have always been home to many newspapers. Even today, three dailies in São Miguel and Diário Insular survive in Terceira.

How did your career at DI begin?

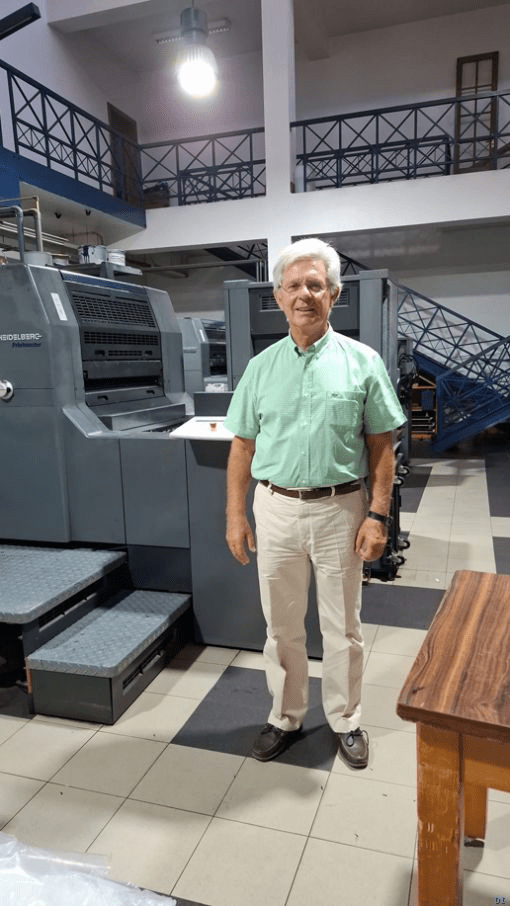

I’ve been working at Diário Insular for over 40 years. I was born in Guarda, studied in Lisbon, and met my wife, an Azorean from Faial by birth but Terceira by life. Then, I naturally headed for the Azores. I was a teacher in Lisbon, also at the Angra Secondary School, and worked in the Regional Administration, but I soon became involved with the DI. I’m now the dean of the directors of the newspapers that still survive in the Azores, so I have a measured view of the graphic arts and paper consumption from my experience.

Is DI more than a newspaper?

DI is also a printing company. In essence, Sociedade Terceirense is a printing company that owns a newspaper, has a printing plant installed, and, in addition to producing the newspaper, produces other work to respond to what remains of a local market.

You mentioned the earthquake of the 80s. How did it mark the transformation of the newspaper?

The earthquake was terrible because the building that served as our premises was complex. It was narrow and very long, and it was on a street that was also narrow. At the time, we worked with typographic machines. Offset hadn’t been born for us yet. We worked in the lead with manual typesetting, and we also had two mechanical typesetters, a Linotype and an Intertype. We had a letterpress, which was a big step forward then. The Heidelberg printing machines were cumbersome and were on the first floor. The only space available for the newsroom was on the second floor, and the small paper warehouse was on the third floor. When the earthquake hit, the building moved so much that the façade separated and no longer returned to its original location, and the building was left on a perilous slope. Despite this, the paper only stopped for a month because we rented part of the front building and a module/container installed in a nearby square for the newsroom, so we continued to produce the paper.

At the beginning of the 1990s, we built a new building overlooking Porto das Pipas on the city’s eastern edge. Then came the technological leap to offset printing, which opened the door to graphic design. Those were very auspicious years of remarkable evolution and market growth of paper consumption, with lots of advertising and lots of subscribers—everything that today is starting to disappear—or rather, to disappear.

How does this impact your business?

It’s causing a decline, with great fears that the disappearance of titles will be irreversible, and then they’ll never come back. Faial used to have two daily newspapers – Correio da Horta and Telégrafo. Both have disappeared. Terceira currently only has the Diário Insular, which is in grave danger of disappearing if the public authorities don’t understand that private and independent newspapers serve the community. Without its newspaper, there is no measuring what an island – in this case, the second largest and most important in the Azores in economic terms – will be.

Given the situation, are you looking at digital technology, for example?

We’ve done some trials with digital technology for small print runs, and my “final cry” – and I still think I have the strength to do it – would be to make a complete migration to digital printing. I don’t intend to do away with offset altogether, the equipment is there, it’s amortized, it’s great and it would be a waste to do so, not least because there are still requests for significant print runs. However, I will embrace a project transforming newspaper printing from offset to digital. This is because a lot is consumed online today, and the demand for paper vehicles is decreasing. This means less ink and plate consumption, waste, and complexity. I recognize a problem with the format and perhaps the type of paper to be used, but we would offer the market another possibility: an on-demand offer. People could come here and order the August 25, 1999 issue, and it would be printed on the spot. At an advanced stage, I’m studying the economic viability and Community support that could be added. But everything points to a rationalization of costs and will result in, I would say, an innovative offer for the local market itself.

How many copies do you currently produce?

We produce 1,500 copies daily; the regular edition is 24 pages, partly in color and partly in black. Digital would be ideal, but it’s not easy to print low-grammage newsprint with a little hand in digital printing. We know it’s the “low-quality paper” that wraps the dishes in the house when we move, that covers the shop windows when they’re being made up… It’s that paper that lasts 24 hours. But that touch, that brownish appearance, is the newspaper’s trademark. In the research we’ve been doing, we’re concluding that papers below 70 g/m2 don’t do well in digital. Currently, the newsprint we use is 52 g/m2. You also have to consider the cost of using other paper… We’ve looked at “book paper”, which is more yellowish, but the costs are substantially different. I’ve realized that the paper must be at least 60 g/m2, with some strength, so it doesn’t curl. Digital technology has evolved, but the temperature of printing systems is still high.

What attracts you most to digital technology?

I think of the alternative it would offer to the local market, to the client who shows up and wants 100 business cards or a 150-copy brochure, whose offset response is disastrous. I think it would complement and make the equipment more profitable, just as offset used to do for medium and large print runs.

What challenges does insularity present when you’re in the graphic arts?

Fundamentally, supply and the need for extensive stockpiling. The Azores are islands far from the mainland, with long sea journeys and prone to bad weather. We have to be stockists; as far as newspapers are concerned, we buy paper yearly for market reasons. Due to the high humidity levels, we must be cautious when storing it. Still, we’ve learned it’s not worth using air conditioning or dehumidifiers because it’s a disaster for the paper. We ask our suppliers to be careful with the packaging and let the paper naturally adapt to the environment of our workshops so that it can perform well in print. We only have one boat a week, and the goods must be shipped to freight forwarders in Porto or Lisbon. If the goods aren’t delivered on time or there’s a problem with the boat, that means a delay of 15 days. I can’t worry about the lack of plates, paint, special liquid, or a particular part. The logistics and costs differ significantly from those of other companies operating on the continent. And when it comes to the newspaper, it’s difficult to “pass on” these costs to our subscribers.

You have a news portal and a PDF newspaper version available to subscribers. How important is this complementary offer?

This was launched when we celebrated our 50th anniversary 27 years ago. It resulted from a partnership with the University of the Azores. It’s an edition that I’d like to be more dynamic than just transposing the paper edition. In any case, subscribers can be exclusively digital, but paper subscribers can access the online edition. However, news aggregators are killing us. Every day, by the hundreds, we receive PDFs of the regional, national, and international press on our cell phones. I even received my newspaper, distributed on WhatsApp, before the day’s edition reached readers. Yes, it’s piracy. It’s a crime. Then, there are the big news aggregators who use our work to make it profitable. There has already been talk of taxing the big technology companies or the big communications operators with a tax similar to the one we pay on our electricity bill, which supports public television and radio. There could be a similar tax so that there is a rational distribution among the media to help them survive. If this doesn’t happen, a large part of the press, especially the tiny regional press, is at risk. We may only be subject to social media, where there is no journalism… there are opinions, there is fake news, and there is replication of strange and unverified things, sometimes with hidden but terrible intentions. The Regional Parliament and the Regional Government must understand the importance of the regional press and act accordingly.

How can this support be done?

There is such a simple way: increase newspaper revenues. The government could distribute subscriptions to all the departments of public administration and those entities that generally sit at the budget table. It could distribute subscriptions to people’s houses, brotherhoods, associations, public services, etc., on all the islands. Here in the Azores, in order to receive the four daily newspapers, these entities would only need to include €1,000 in their annual budget. Another way to increase newspaper revenues would be to buy advertising in advance, as they did during the COVID-19 pandemic. The advance purchase, which would be used throughout the year for information and awareness campaigns as they saw fit, would perhaps be enough to help the newspapers’ sustainability.

How is DI still maintained?

With great sacrifice and a significant investment of its members’ personal savings in the newspaper, which is running out. With management “on a knife edge” regarding human and technological resources. It’s evident that maintenance is being postponed or “botched.” However, there is a window of opportunity: we have been working with the regional government to find ways to overcome this crisis. We are committed and hope that a support program will be approved to replace the current system, which is entirely ineffective and insufficient. The only significant support currently exists is support for distribution, which in our case is limited to the CTT bill and a few crumbs for energy and communications. The government is aware that it is necessary to value the role of the media in a region as dispersed and heterogeneous in its development as the Azores and that, in this way, it is building a sustainable future. However, the proposals will still be presented and discussed in the Legislative Assembly, and we hope that a consensus will emerge. But, I repeat, what the media companies need is more revenue. They need to sell more newspapers and advertising in order to provide an impartial public service.

And could this be achieved, for example, by raising awareness in society, especially among the younger generation?

Of course, it could. I’m always open to collaborating with local schools, for example. In fact, I’ve cherished a school newspaper for over 20 years, the Biscoitinho, which I include in our edition. It’s an exciting project that should be copied in the region and country. On the other hand, I think people feel that their newspaper is essential. We hear it in conversations in cafés, gatherings, and approaches. Everything here is very personal. But the next step is missing…

In addition to public support, do you think it will be possible to change mentalities so that the business community also sees the newspaper as a more effective vehicle for transmitting its messages?

Terceira is a fantastic island in many ways, including culturally. It’s the second-largest island in terms of population. Still, it’s a size that complicates everything because it doesn’t have a sufficiently large and robust business fabric to free up the means to support a newspaper. This is the harsh reality. Why does the press survive in São Miguel? Açoriano Oriental is a case in point because it belongs to a large national media group and will probably have other problems, but it will also have different facilities. However, other newspapers survive thanks to the size of the market. Here, companies are increasingly looking at digital media. They want the newspaper to make the news, but they don’t consider betting on the small budget they have to invest in advertising the newspaper. Either there is a commitment on the part of the public media – whether municipal or regional government – that provides concrete support but does not create “subsidy dependency,” or the near future will be bleak. Subsidies almost always mean that there is no “free lunch,” and there are always constraints, even mental ones. That’s why I argue that newspapers must sell goods and services, which is entirely different. There’s so much that the public authorities can do that the official newspaper doesn’t because that’s not its purpose. It can run educational campaigns on health and eating habits, promote civic attitudes, and call for civic and political participation. All of this can be translated into good advertising and, by the way, well paid for.

Translated to English as a community outreach program from the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI) and the Modern and Classical Languages and Literatures Department (MCLL) as part of Bruma Publication and ADMA (Azores-Diaspora Media Alliance) at California State University, Fresno, PBBI thanks Luso-American Education Foundation for sponsoring PBBI, including this platform..