What was April 25th?

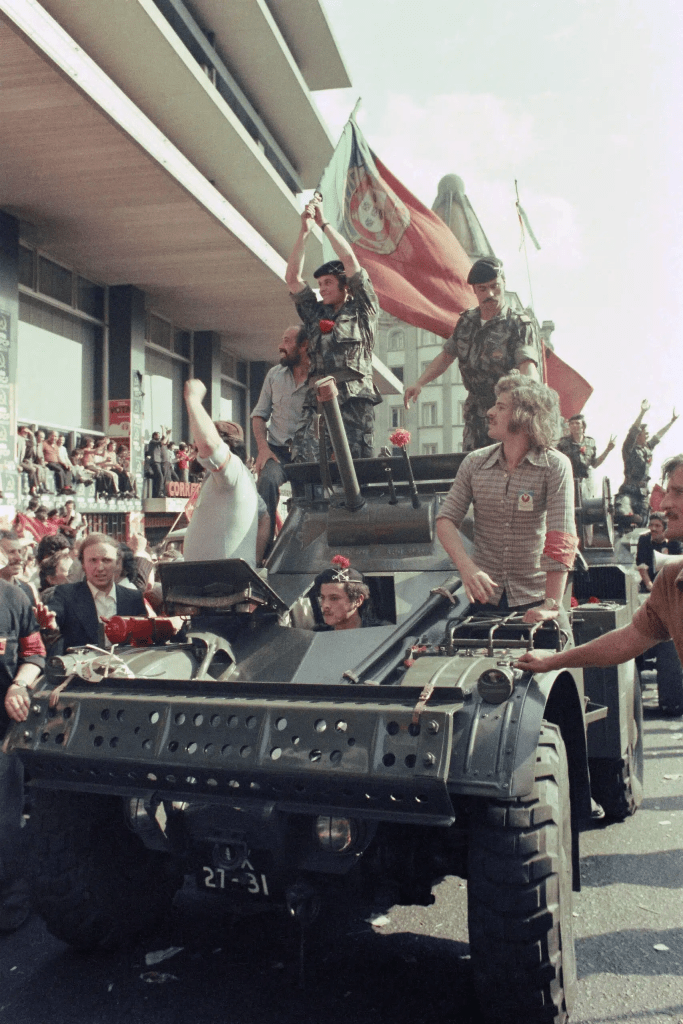

When, on April 25, 1974, a group of young captains carried out a coup d’état that, in less than 24 hours, overthrew the dictatorship that had dominated Portugal for over four decades, the course of national history changed decisively.

Their lives, as well as those of thousands of Portuguese, were about to change radically. Soon, the coup gave way to a Revolution that, for almost two years, shook the country, opening up a wide range of possibilities for the future.

Colonial war

There is a broad consensus that the trigger for April 25 was the colonial war, which began in Angola in 1961 and quickly spread to new fronts (Guinea, 1963; Mozambique, 1964), with no military solution.

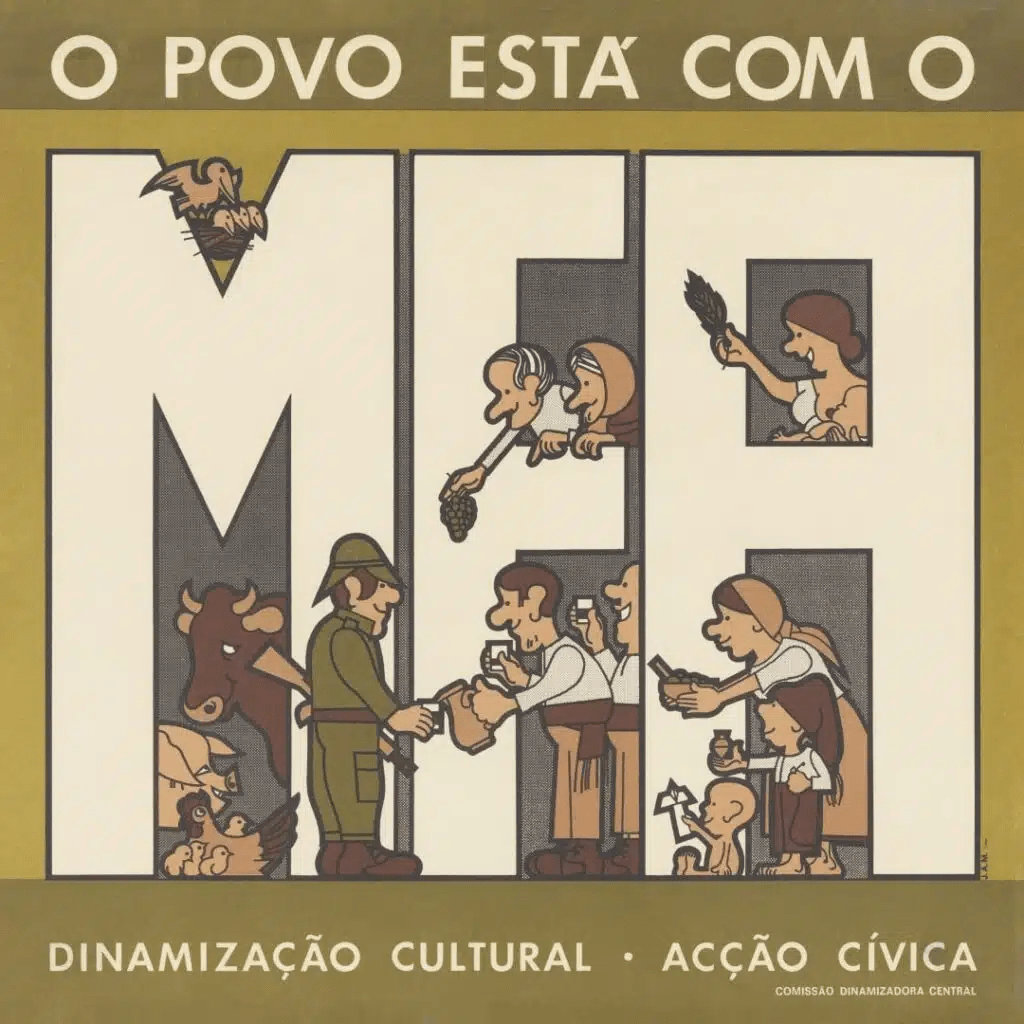

The war had a deadly effect on the Armed Forces, one of the regime’s central pillars, contributing decisively to the radicalization of opposition and social protest against the Estado Novo. In response to new legislation aimed at compensating for the shortage of officers at the front in Africa, the Captains’ Movement/Movimento das Forças Armadas was formed in September 1973.

The conspiratorial phase was relatively brief, giving way to a rapid process of politicization of the Movement. The signs that the end of the regime was imminent, given its intransigence in maintaining the war effort, grew more substantial from the beginning of 1974, including the publication of Portugal e o Futuro (February 22), the ceremony of the “rheumatic brigade” (March 14), the resignation of Generals Costa Gomes and António de Spínola as heads of the General Staff of the Armed Forces (March 15) and the false departure of Infantry Regiment no. 5, from Caldas da Rainha. 5 Infantry Regiment in Caldas da Rainha (March 16).

International impact

The impact of the captains’ intervention quickly transcended national borders in a world divided by the Cold War and shaken by the recent oil crisis. Those who promptly drew parallels between these events and those that had occurred a year earlier in Chile (“Pinochet coup”) were quickly disillusioned.

Denying all the most common models of military intervention in political change processes, the coup was carried out by the middle ranks (captains and junior officers), outside the hierarchy of the Armed Forces, and without the interference of political parties or movements.

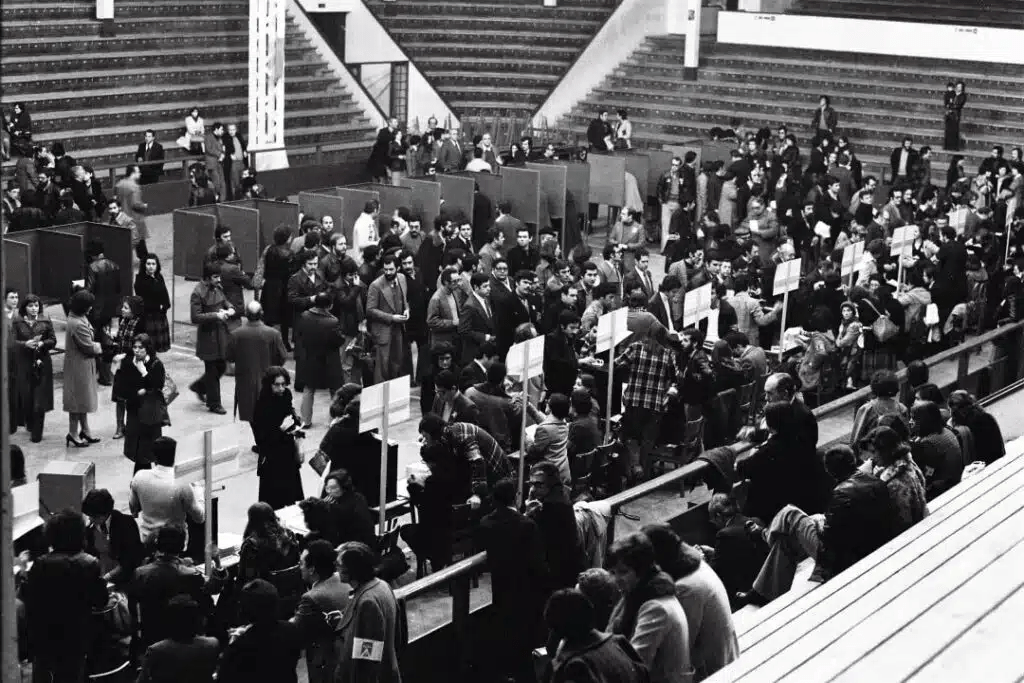

Furthermore, the Captains of April presented a democratization programme which, in addition to restoring fundamental freedoms, called for establishing a civilian government and holding free elections.

In the same way, unpredictably, after more than a decade of fighting on the fronts of Africa, they began a process of decolonization that soon resulted in the granting of independence to the former colonial peoples. This unique situation caught the academic community off guard and the world’s ruling elites, who were faced with the difficult task of integrating the Portuguese case into the established analysis grid.

Two interpretations

Studies on April 25, 1974, have oscillated between two opposing interpretative lines. On the one hand, some emphasize its pioneering spirit, presenting it as a precursor to the third wave of transitions to democracy. On the other hand, those who emphasize its “backwardness” affiliating it with past revolutionary movements. Adopting the expression coined by S. Huntington, the first line presents April 25 as the inaugurator of the wave of democratization in the last third of the 20th century. Anticipating the end of the Greek military dictatorship in three months, Adolfo Suárez’s agreed transition in Spain in two years, and the transitions in South America and Eastern Europe in one and two decades, respectively, the Portuguese experience opened up new angles of analysis on political change and, more particularly, on democratization processes.

These and other realities have led some authors to question the idea that Portugal was a forerunner of the third wave of transitions to democracy, highlighting instead its backwardness. Affiliating April 25 with the transformations inaugurated with the military defeat of conservative authoritarian regimes during World War II, they present April 25 as a renewed 1945 with ingredients from May 1968, dates lost in Portugal in their original editions. Thus, rather than a pioneering movement, 25 April should be presented as the last example of a series of decolonizations of colonial empires and a failed transition to socialism.

Seen from the outside

The originality of the Portuguese transition was immediately noted by the international press. On May 6, 1974, Newsweek drew attention to the fact that the Portuguese had always shown a “very unique way” of doing “things,” using as an example the fact that “even that bloody Iberian spectacle, the bullfight,” acquired in Portugal “a special, gentlemanly characteristic, because the bull is never killed.”

All those who observed Portugal’s political evolution from the outside in 1974-1975 are unanimous in pointing out its exceptionality. Le Monde journalist Dominique Pouchin refers to it as the “last Leninist theater”, a “Cuba in Southern Europe”. The cultural tourism trips organized by the Nouvelles Frontières agency show that, for young Europeans fresh from the May 68 experience, this was a chance to see in situ what they only knew from textbooks. Portugal was a political and social analysis laboratory where Europe’s last left-wing revolution occurred.

The events of the Revolution

The 19 months of the revolution were full of events: three failed attempts at a coup d’état; six provisional governments; two Presidents of the Republic; the intervention of the military in politics; the alliances that its various sectors established with different political groups and social movements; the action of political parties and movements; nationalizations and the triggering of land reform; experiments in workers’ control and self-management; the multiplication of popular initiatives; the República and Renascença cases and all the turbulence that ran through the media field; the Western powers’ distrust of Portugal becoming a Trojan horse for NATO; the debate about the essence of Portuguese socialism, allowing radical experiences and conceptions to coexist with more traditional political projects that pointed towards the establishment of a Western-style parliamentary democracy or a statist model inspired by the Soviet experience; the overwhelming weight of politics flooding the streets, the barracks, the factories and the countryside.

All the possibilities were open, but this was “the possible and lucid Revolution” (Eduardo Lourenço).