THE (TENTH) ISLAND OF SANTA CATARINA

The origin of Azorean emigration may go back to the beginnings of settlement.

We have always been – and still are – an emigrant people.

The five major Azorean emigration destinations arranged chronologically were Brazil, the United States of America, Bermuda, Hawaii, and Canada.

Our first Atlantic destination was the “Vera Cruz” lands of Pedro Álvares Cabral.

During the colonial period, in the 17th and 18th centuries, the Portuguese Crown disciplined promoted, and financed the first emigration.

Thousands of Azoreans left their archipelago for the “land of oblivion” to occupy and develop new colonial areas of Brazilian territory – both in the Amazon basin of Pará and Maranhão and on the southern coast of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul.

The first Azoreans left for the state of Maranhão in 1619.

Two hundred couples from the island of Faial left for Pará in 1666.

In the following century, the first governor of the captaincy of Santa Catarina, José da Silva Paes, developed his project to systematically occupy southern Brazil with couples from the Azores archipelago.

This is how the basic nuclei of the Santa Catarina coast were formed, with around 4,500 Azoreans, especially in Desterro and Laguna.

In just eight years, from 1748 to 56, six more local communities were born with Azorean blood: Santo António, São José, São Miguel (Biguaçu), Enseada de Brito (Palhoça), Lagoa da Conceição, and Vila Nova (Imbituba).

It was with 400 of these Azorean couples that the social organization of Rio Grande do Sul began to be structured, starting in 1751.

Along more than 500 kilometers of the Santa Catarina coast and almost 1,000 kilometers of the Rio Grande do Sul coast, the 6,000 Azoreans who overcame an Atlantic crossing of more than 8,000 kilometers less than three centuries ago have grown and multiplied.

The Government of the Azores estimates that there are around 1.5 million descendants of Azoreans, predominantly in Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul.

The second period of Azorean emigration to Brazil, in the 19th and 20th centuries, is now mainly aimed at São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Salvador.

In the meantime, the numbers are falling: from 13,000 annual departures in the 1960s to around 1,000 in the 1980s.

But the Azorean blood that runs through Brazilian veins is still – and forever – very much from the south.

That’s why today we can consider Santa Catarina the tenth island of Azoreans in the Atlantic…

We could even say that the island of Santa Catarina was God’s best way of making southern Brazil less distant from the Azores and a lot more like its paternal archipelago.

Culturally, Santa Catarina is an accomplice of all the nine islands of the Azores.

Physically, it resembles the archipelago’s largest island, São Miguel.

They are unequal in surface area – Santa Catarina has 400 square kilometers, and São Miguel has 750.

They are even more unequal in population density—Santa Catarina has 620 inhabitants per square kilometer, and São Miguel has 180.

But they are indeed very similar in shape:

Santa Catarina is 54 kilometers long, and São Miguel is 64.

In maximum width, Santa Catarina is 18 kilometers and São Miguel 16.

They are also unequal in relief – the highest point in Santa Catarina, Morro do Ribeirão, is half the 1,100 meters of Pico da Vara, the summit of São Miguel.

However, they are also similar in terms of hydrography—each has around 20 lagoons, although the three largest and most emblematic lagoons in São Miguel (Lagoa das Sete Cidades, Lagoa do Fogo and Lagoa das Furnas) would fit together in the 20 square kilometers of Lagoa da Conceição, in Santa Catarina.

After all, the biggest difference lies in the smaller distance: São Miguel is 1,600 kilometers from the Portuguese mainland, and Santa Catarina is only 500 meters from the Brazilian mainland.

With their differences and similarities, the big conclusion is that Santa Catarina and its “Azorean sisters” are physically beautiful and culturally rich islands.

That’s why it’s worth setting off from this tenth island to bet on a transatlantic archipelago of cultural complicities.

The culture that unites us is much greater than the sea that separates us.

We need to keep building bridges… such as the Hercílio Luz Bridge, which will reach the other side of the Atlantic.

Translated by Diniz Borges

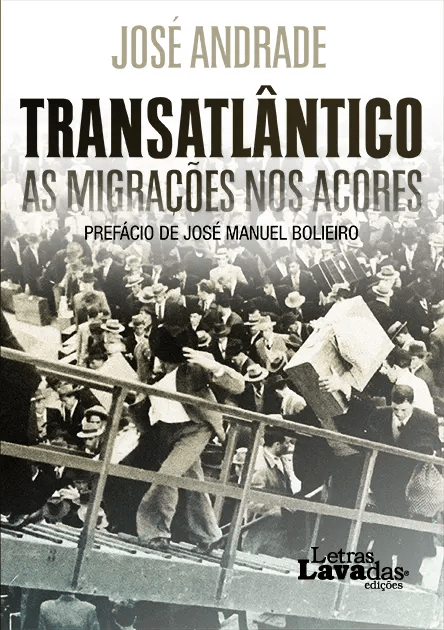

José Andrade is the Regional Director for Communities in the Government of the Autonomous Region of the Azores – From his book Transatlântico – As Migrações nos Açores (2023)