Dear Young Person:

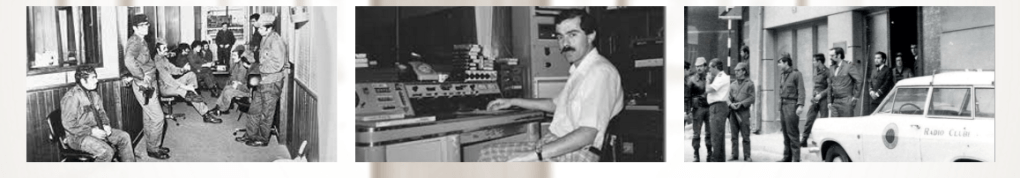

April 25th was a generous action planned and carried out by a group of young Armed Forces Movement (MFA) soldiers to solve complex problems. In 1974, Portugal was a backward and closed country, with more than 30% illiteracy, governed by an authoritarian, autocratic and corporatist political regime, 41 years old, sustained by a repressive apparatus that curbed all individual and political freedoms, which offered the Portuguese poor living conditions, particularly in rural areas; with a stagnant agricultural sector and a limited and underdeveloped industrial sector, which led to the emigration of almost two million Portuguese to Western Europe and America or, alternatively, to migration to the outskirts of the big cities with an exponential increase in shantytowns and clandestine housing, without basic sanitation, associated with extreme phenomena of poverty, social exclusion, crime and prostitution; which since 1961 had maintained an annual average of 105,000 men involved in three war fronts in Africa, 54,000 in Angola, 20,000 in Guinea and 31,000 in Mozambique, reaching a total of 148,090 men in 1973; in a war whose end was totally unpredictable and where more than 800,000 men fought, of which around 70 percent were recruited in the Metropolis through compulsory military service that lasted 4 years, which caused the death of 8,831 Portuguese, the physical disability of nearly 14,000 and psychological trauma in around 140,000. It was this severe and complex situation that the young soldiers of the MFA decided to resolve.

But April 25 was also an exercise in critical thinking. In the military institution, one of the mainstays of the regime, directly engaged in a war in which the signs of saturation were evident, the political measures taken by the government to ensure the survival of the regime and the perpetuation of the war had a significant impact. Depending on their degree of political awareness, a considerable number of young soldiers from the three branches of the Armed Forces began to discuss the issue of the war and the very nature of the regime more or less openly. In June 1973, the 1st Congress of Overseas Combatants, an initiative of the nationalist right and the radical sectors of the political establishment and the government aimed to push through the concept that the solution to the Overseas War was military and that it was necessary to reinforce the war effort. In response, the Army’s permanent staff collected signatures by telegram to challenge Congress’s objectives. They were ultimately successful because they completely emptied Congress by sending and circulating a telegram signed by more than 400 permanent officers stating that they would not recognize any decision approved by Congress. Furthermore, this military demonstration was of fundamental importance in the action leading to April 25. In fact, the military protesters became aware of their own strength and the weakness of power by gaining more than 400 members in a short time in a public demonstration of insubordination without suffering any reprisals. The fact is that, in the light of the military regulations in force, the collection of signatures was, in fact, a collective act of indiscipline on the part of the Permanent Staff officers.

For internal and external reasons, the conditions were in place for a revolt to break out; all that was missing was a trigger. It came when, on July 13, 1973, following the Combatants’ Congress, the government published the notorious Decree-Law 353/73, which changed the seniority count for militia officers entering the Army’s Permanent Staff and reduced the duration of the particular course at the Military Academy to just one year, followed by a six-month internship. These measures, intended to make up for the lack of QP captains to command companies in the war, were unacceptable for officers from the Military Academy. As early as July 17, and taking advantage of a visit by the director of the Personnel Service of the Ministry of the Army to the Institute of Higher Military Studies, a group of military personnel attending the Institute presented him with the first of several presentations contesting the decree. This was the genesis of the Captains’ Movement, created to defend the interests of the class of Army QP captains. The first meeting of the nucleus took place on August 21, 1973, and its name was inspired by a corporate concern.

However, the Captains’ Movement, which effectively represented a minority of Army QP officers, no more than 700 out of 4,165, underwent a rapid evolutionary process and, in December 1973, was renamed the Armed Forces Officers’ Movement. This name evolved in the final phase to MFA. The Movement’s support base grew as the plenary meetings took place, the corporate issue losing ground to other objectives, among which the dignification of the Armed Forces and the political solution to the war was the most significant, even though the government, alarmed by the repercussions of the measures initially taken, tried to mitigate some aspects. Convinced of the exclusively corporate nature of the young officers’ discontent, the government tried to demobilize them with the annulment of the decree and a substantial pay rise, particularly for captains, whose pay was increased by 40% towards the end of 1973. However, the growing political awareness of the Movement and the conviction that the war would only be resolved if the government was overthrown had made the process irreversible. In addition, the accession of members from other branches of the Armed Forces, the Navy, and the Air Force made the Movement much broader regarding objectives and participants. In this spirit and with this awareness, elements who would join the Movement attended the Third Congress of the Democratic Opposition in Aveiro in 1973. The Aveiro theses would inspire the MFA Program as an ideology of freedom, peace, and democracy. Thus, although the Captains’ Movement originated the MFA, it does not correspond to the same political and sociological reality. Some officers belonged to the former and were not in the latter, just as some of the officers who were part of the MFA did not belong to the Captains’ Movement.

Under the conditions of the regime in power in Portugal, the plotting and preparation of the military action on April 25 also had to be an exercise in creativity. Evidence of this creativity can be found throughout the MFA’s maturation process, in the preparation and conduct of the preparatory and coordination meetings, in strict respect for the principles of representativeness and democracy, in the way the adherents were informed and kept informed of the main decisions, in the drafting of the Operations Plan and its Annex of Transmissions, all in a context in which the opposing forces were incomparably more potent than the insurgents. In a process that lasted around nine months, in which it was necessary to counter and deceive the initiatives and actions of the government and its military and police apparatus, only a formidable exercise in creativity can explain the surprise with which the government belatedly became aware of the movement of thousands of military insurgents across the country in the early hours of April 25, 1974.

The short maturation period of the MFA and the conditions of the conspiracy did not allow everyone to internalize a consistent political and ideological vision. It did, however, make it possible to draw up a political program for the period of transition to democracy, the MFA Program, the spirit of which is clear regarding the transition of power to civilian political forces and the non-continuation of the MFA and the Armed Forces in the exercise of power beyond the transition period, as well as the right of the peoples of the colonies to self-determination and independence and the development of Portuguese society in a progressive direction for the benefit of the most disadvantaged classes. This was the most remarkable historical singularity of April 25 and the final proof of the April military’s creativity. They took power to establish democracy and freedom, initiating a global democratization process in Europe, South America, and elsewhere.

However, the successful preparation and execution of the military coup and the operations throughout April 25 were also an exercise in team management worthy of mention. It was the team management skills of the MFA’s young officers, acquired in the theaters of war in Africa, that allowed a small core of a few hundred to mobilize and commit thousands of other officers, sergeants, and soldiers to the execution of the Operations Plan, all within a few hours. The leadership qualities of the Movement’s leaders and the trust of their subordinates were undoubtedly decisive in the whole process.

But if team management was decisive for the success of the military operations, the ability to coordinate with others became of paramount importance from the morning of April 25, first in the confrontation and negotiation with the opposing forces and with the hegemonic tendencies that soon manifested themselves within the new military-political power, and then in the relationship with civil society and with political and the party troops. As soon as the Movement became victorious, the MFA military had to work with others in entirely new conditions, trying to carry out their program in a complex environment subject to unpredictable social and political dynamics. The whole process up to the entry into force of the Constitution on April 25, 1976, which was highly complex and at times on the brink of disastrous confrontations for the Portuguese people, showed that the majority of the military personnel who were involved on April 25 in one way or another were able to ensure that the fundamentals of what had led the Movement to move towards the overthrow of the Estado Novo were nevertheless preserved.

In just two years, Portugal underwent the most profound change in its history, not only in the political system but also in social and economic concepts, structures, and relations. At the heart of this change have always been the April soldiers and their skills in solving complex problems, critical thinking, creativity, team management, and coordination with others. The same skills that today are decisive for the success of young people in the job market!

That’s why April 25 can be a reference point for today’s young people and a challenge for them to try something new according to their conscience, even at the risk of doing so. And when today’s young people study and debate the problems that affect them and seek solutions, just like the young soldiers of April, in exercising citizenship and building a fairer society, I have confidence in the future. I am confident that they will be true entrepreneurs, not in the individualistic sense of the concept, but by the values of freedom, solidarity, inclusion of the most disadvantaged, and social progress. I am confident that you will be able to resist the instruments of submission, however seductive they may be, and, inspired by the words of Vergílio Ferreira, say NO to what limits and degrades you and build the YES of your Dignity.

Greetings from April,

Jorge Bettencourt

(a military member from the April Movement- a retired Portuguese Navy commander). He is also a member of the Associação 25 de Abril.

Our guest at Fresno State to COmmemorate the 50th anniversary of the 25 de Abril-the Carnation Revolution. We are thankful for his willingness to travel so far to commemorate this historical date with our students, faculty, staff, and community.