“The Insularity of the Poet”

The island had the madness of my ten years, the age at which I left it. They called it Green, a name that my memory has accepted. Not because the island held the classic image of impetuous vegetation from which its epithet comes but because Green was the throne I placed in the solitary room of my childhood. I’m referring to a bench against the wall of a convent fence, where, under an anchor entwined with the word hope, Antero tragically consummated the irony of his life disputed by light and darkness. It was this bench that I used to take refuge in when, in the afternoon, in Campo de São Francisco, I would sneak away from the other children, mysteriously drawn to the green throne where the poet had seated his suicidal majesty, finally seeking in death the meaning of freedom that he had vainly pursued in life.

Flying over a milky orography of clouds, the Boeing 727 sweeps me relentlessly into a world of ghosts whose proximity squeezes my stomach like agony. In their impeccable service, the hospitable TAP air hostesses seem to guess with their care the expectant anguish with which I vertiginously descend the slope of my return. Down? No. I’m going to challenge the ghosts of childhood. To challenge is to grow.

A drop of honey in a sea of lead. It’s Santa Maria. It was a sign of rain when we glimpsed it from afar, from the Aterro. They say the Aterro no longer exists. Who stole this observatory of the impossible from my childhood? Who else would they have taken from me? Take everything but Antero’s bench. There, I shyly thought I was different from the other children. Now, I’m determined to reclaim my fantastic childhood possessions. The house in Rua dos Mercadores with aunts named after flowers, whipped by the wind that blew the grandmother’s poetic dementia. And in the center, mother, making the glossy black piano laugh and cry. Hurry up, captain of this airship! Fly your ship at the speed of blood rushing to the source.

As the car pulled away from the airport on its way to Ponta Delgada, my heart groped and recognized the surroundings of the poet’s seat. I spot him in the distance, in the field of São Francisco. But I put it off. I want to reconstruct the map of sensations where Antero’s bench occurred naturally as the last of the coherences of an introverted, serenely extravagant cosmos.

Stepping on mosaics that reproduce pineapples and ears of corn, my steps lead me to the square of the Mother Church. Everything is intact. There’s the Café Central, the city’s old liar; the Clube Micaelense, frowning for the last century at bad reputations when they weren’t gilded by blood or money. Who said I’d been robbed of the Aterro? That was a lie. Here it is, stubbornly implicit in its old place, now a section of the seafront, humanely reconstituted by the people who continue to eat there, hereditarily attached to that place that existed for people to want to embark. Not to leave the island but to find it outside of it. That’s the islander. The man who is where he isn’t: Antero. His extremes and discrepancies are explosions of a purely insular idiosyncrasy. “There must be – he writes from the Azores to Oliveira Martins – a deep relationship between man and the land where he was born and raised.” He confesses that “that isolation in a corner of the world that is already a half-death or an anticipated death” suits his mood very well. He would like to settle there for good. But in the summer, he’s already on his way back—a postponed suicide escape. The island is an implacable mirror that doesn’t allow him the spiritual trick of an idealistic optimism that his nerves can’t stand. In vain does he ask reason to communicate to his nerves “the stoicism it has, but which they don’t seem susceptible to.” To Oliveira Martins, he confides this last message of his discouragement. It’s the preamble to the big decision. This time, the island wouldn’t let him suffocate the torrent of painful conflicts that wanted to be lost in the sea of death. On a warm and humid September day, shackles of low, gloomy clouds imprisoned him within reality itself: his cruciform black and white animal drama. Yes, this time, there is no escape. The white houses with dark stonework are the shameless extroversion of the crossroads of pessimism and utopia that screams at his spirit: “You won’t get out of here.” The island undresses him. Antero is naked and hides in death, which appears to him in the form of an anchor. The poet’s terrible ambiguity becomes absolute: despair is consummated in the shadow of hope. The instinct of light breaking through the darkness.

The veil enveloping the bench is torn. The pretexts for postponing the meeting disappear. I’m standing before you, the old throne of my difficult childhood. You are no longer the question mark with which I interrogated my sphinx. You’re a period. I’ve retraced the paths that led to you. Flanking the craters’ edges, I traverse the cruciform landscape as if exploring the abysses of the poet’s soul—an endless unfolding of contrasts. The infamous, strangely aureolated by a Scottish climate, wade in the warm, muddy water. Thus, Antero, the oriental feast of your skepticism in the cold marble hall of your European rationalism. Hence, Antero, in the rough and dark bed of affable beauty, your intermittences of frenzy and sweetness, the earthquakes of your spirit, the convulsions of impotence that makes you a philosopher and the lyrical repose of a dream in which you listen to the sighing of things. Now, a valley of ferns opens up like a fan behind which paradise winks at us. A mischievous invitation because right in front of us, Hades is baring its teeth at us in the Pero Botelho Caldeira (crater). A dark rift like this gave rise to the myth of Vulcan’s mansion, and so, Antero, your prayer to absent perfection. But it is the genius of the night, the infernal weaver of shadows, who hears it.

Finally, the island wonders: is this what remains of Atlantis, the last flower of the submerged continent, or a bunch of cliffs that the bottom of the sea has thrown up? The island wonders hamletically like Antero: To be or not to be? The island of Medea is the mother and devourer of the poet.

Translated by Diniz Borges

Natália Correia(1969). «O poeta e o mundo», «A insularidade do poeta». Diário de Notícias, 16 de Outubro, pp. 17-18.

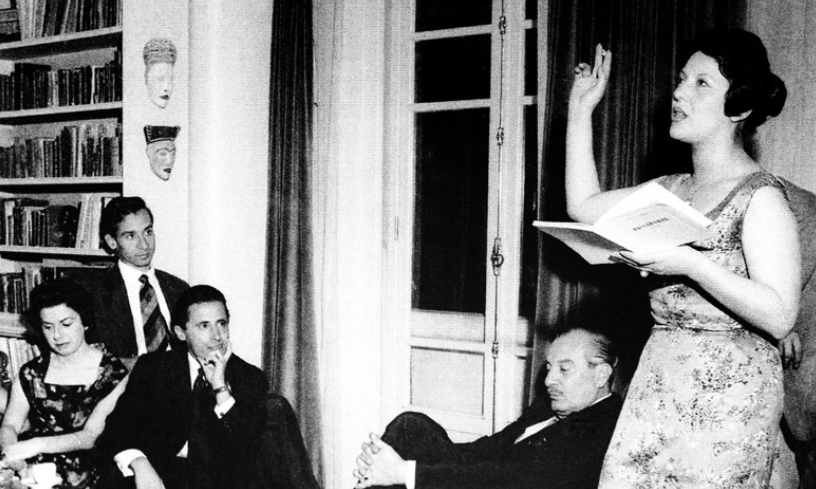

A weekly segment with translated works from Natália Correia as part of the Cátedra Natálai Correia from PBBI-Fresno State.