More memories from half a century ago by João Bosco Mota Amaral

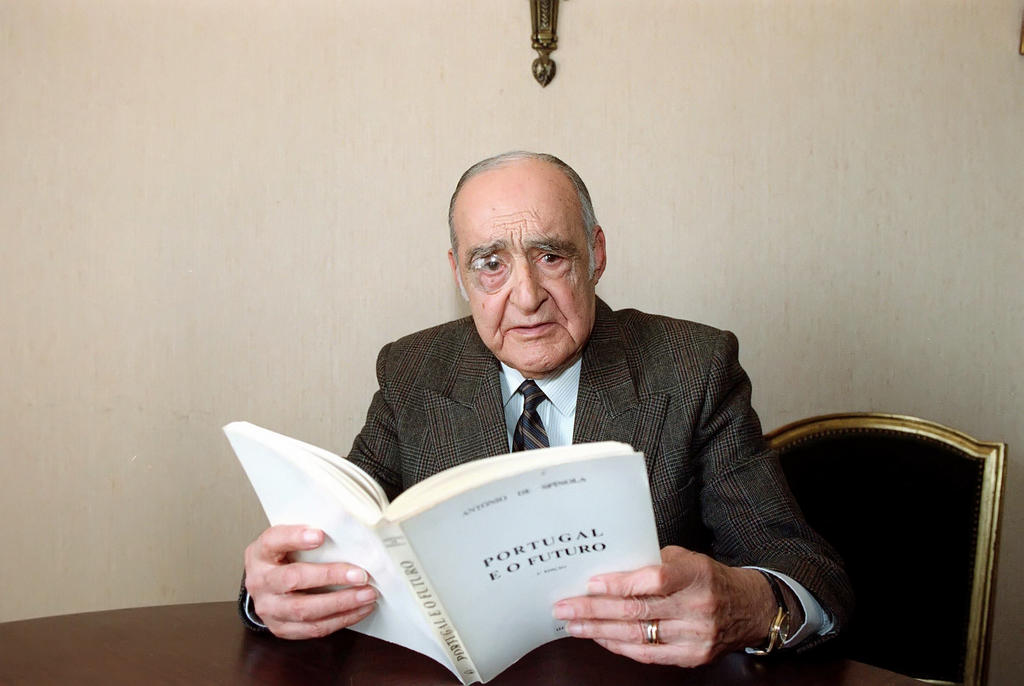

It will be 50 years, give or take a few days, since António de Spínola’s book “Portugal and the Future” appeared on the shelves of bookstores and soon became a real publishing success, with five editions eagerly sold out by a wide readership. Incidentally, I found a copy of the third edition, signed by the first owner, with the date and everything, on sale for a symbolic price in our Public Library, and I didn’t hesitate to buy it to re-read the main passages. Naturally, I have the book, but I don’t know where it is, and the opportunity to revisit it is now or never…

The political scandal caused by the book in 1974 was because its author was the Governor and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces in Guinea, where he distinguished himself by conducting military operations near the troops on the ground. In addition, he tried an intense dialogue with the tribal chiefs, organizing a Congress of the People of Guinea, where a future political-administrative statute for the territory was discussed within the framework of the recent constitutional revision, which had opened the door to Progressive and Participatory Autonomy for the then Overseas Territories, under the policy defined by Marcelo Caetano. (Needless to say, the draft Statute of Guinea was very much cut down by the National Assembly, as were those of the other Overseas Provinces, in obedience to the colonialist principles shared by the overwhelming majority of its members. The same had already happened in the early days of Constitutionalism, leading to Brazil’s independence).

So, what was the fundamental point of Spínola’s book? The formal recognition

that a guerrilla war such as the one that the Portuguese Armed Forces had been fighting for thirteen years, by the decision of the Salazar government, could be lost but could not be won. This, said by the Deputy Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces and with the express support of the respective Chief, General Costa Gomes, amounted to discrediting the course pursued by the government and was bound to have serious political consequences.

The book came out on the eve of the Carnaval vacation and was devoured by readers who took advantage of it. Marcelo Caetano, head of the government then, took it with him to read during those days. When he returned to Lisbon, he presented his resignation to the President of the Republic, suggesting that he call in the military chiefs and hand over power to them since they differed from the government in office on fundamental matters. It seems that Admiral Thomaz, regarded as a figurehead, refused the request and the suggestion and ordered the President of the Council to remain in his post and dismiss the military chiefs. And so it was done, with the consequences known to all!

Spínola called for independence for the colonies through referendums and advocated the establishment of a Portuguese Community, which would bring all the new states closer to their former Mother Country. A similar proposal had been formulated by Marcelo Caetano in the opinion drawn up by the Corporative Chamber regarding the 1951 constitutional revision, when the Colonial Act was incorporated into the 1933 Constitution, preparing for Portugal’s future accession to the United Nations Organization, whose anti-imperialist and anti-colonialist principles, with a view to the self-determination and independence of the territories under colonial domination, were included in its Charter and were therefore imperative.

But such a solution was outdated by the passage of time and the critical events that had taken place in the meantime, the main one being the emergence of the Liberation Movements and the guerrilla war they waged on three fronts, with ample international support. In Guinea itself, independence had already been proclaimed by the PAIGC in September 1973 and was even recognized by a large group of countries.

Having taken over the presidency of the Junta de Salvação Nacional (National Salvation Junta) after April 25 and then the post of President of the Republic, Spínola still tried to impose the course advocated in his book. Still, he was not allowed to do so by the leaders of the Armed Forces Movement, who, in line with the sentiments of the people who were expressing themselves on the streets at the time, wanted to end the war immediately and open negotiations with the heads of the Liberation Movements, to transfer power and achieve independence for the territories as soon as possible.

In a dramatic speech in August of that year, the President of the Republic, António de Spínola, recognized the rights of the peoples of the colonial territories dominated by Portugal to self-determination and independence. Due to the popular uprising with arms in hand, it was understood that self-determination had been achieved without needing referendums.

Therefore, the theses put forward in the book proved outdated. The only way open to Spí- nola was to resign as president, which, in fact, happened after the events of September 28, 1974.

This article was printed in Diário dos Açores, Osvaldo Cabral, director.

João Bosco Mota Amaral is a crucial figure in the Azorean Atonomy and the Portuguese political scene, having served for almost 20 years as President of the Regional Government of the Azores, a deputy in the National Assembly, and becoming the Portuguese Parliament’s president. He is now a visiting professor at the University of the Azores and a regular contributor to Azorean newspapers.

Translated to English as a community outreach program from the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI) and the Modern and Classical Languages and Cultures Department (MCLL) as part of Bruma Publication and ADMA (Azores-Diaspora Media Alliance) at California State University, Fresno–PBBI thanks the sponsorship of the Luso-American Development Foundation from Lisbon, Portugal (FLAD)