(followed by Englsih Translation)

From Getty Images

Com tantas dissonâncias na minha vida aprendi verdadeiramente

a preferir não estar sempre certo e marginalizado.

Edward W. Said, Out of Place

É Natal para os cristãos e para muitos outros que o celebram por respeito ou por crenças muito próximas de nós. Quanto à epígrafe, identificarei o autor e as suas palavras noutras linhas deste texto. A realidade é que o mundo está numa ebulição aterradora – guerra por toda a parte, fome, perseguição, morte. A própria Natureza está revoltada. Permitam-me umas breves palavras pessoais. Em 1973 acontece a Guerra de Yom Kippur, em que vários países árabes atacaram Israel – que havia sido fundada por vontade de boa parte do mundo – com o propósito de varrer o relativamente novo país fora do mapa. Eu andava ainda todos os dias na minha faculdade da Universidade Estadual da Califórnia, Fullerton, como aluno a especializar-me também em literatura norte-americana. Nessa altura, Portugal era um país muito distante para mim, de quando em quando olhava o meu Bilhete de Identidade, e já não me reconhecia, nem sequer o meu passado após ter saído dos Açores aos 13 anos de idade, e quando o fazia sentia vergonha do que acontecia em África, mesmo com a pouca informação que me chegava através da imprensa. Tinha lido que toda a Europa tinha vetado o voo de caças americanos para auxiliar Israel numa guerra que diziam “desigual”. Portugal tinha sido o único a colaborar quando cedeu a Base das Lajes para o auxílio do país sob ataque. Na altura, pensava eu, que num gesto solidariedade para com o Estado Judaico. Até saber que tinha sido imposto pelos EUA, o falecido Henry Kissinger no que era o seu habitual modo chantagista perante este aliado pobre sem qualquer poder devido à sua “defesa” periclitante na questão colonial. Atravesso um dia o jardim da minha universidade durante o combate no Médio Oriente, a que não prestei muita atenção, e um colega desconhecido levanta-se de um grupo sentado num banco de lazer e vista larga. Apresentou-se e disse-me: disseram-nos que és português e das ilhas açorianas. Olhei para ele com certa desconfiança e perplexidade. Posso-te dar um abraço, perguntou-me ele. Sim, disse-lhe, ainda com certa desconfiança. Deu-me um abraço, e disse-me em voz baixa: Obrigado ao teu país e às tuas ilhas por permitir a ajuda a Israel. Encolhi os ombros, e mais nada disse, mas não conhecia em pormenor o que me dizia. Não esqueço, nunca esqueci esse momento. Apesar de tudo, senti-me orgulhoso não sei bem de que. Nessa altura, tudo o que dizia respeito a Israel nos Estados Unidos era apoiado cegamente – pensava eu. Israel era uma espécie de país sagrado, a consciência magoada dos Estados Unidos pouco me dizia, sabendo que eles nada tinham feito para salvar os perseguidos em toda a Europa durante a perseguição e Holocausto em curso pelos nazis.

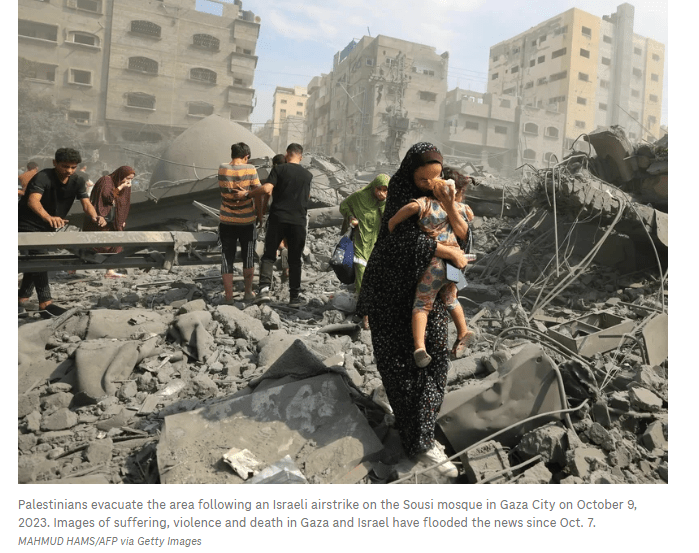

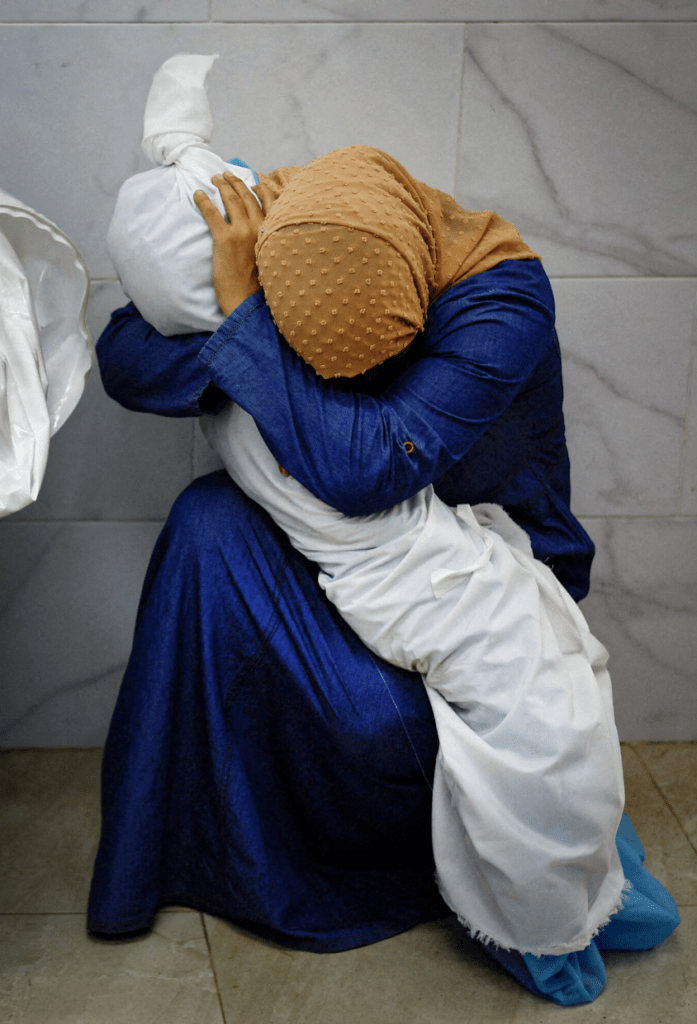

Eu já tinha lido muito sobre o Holocausto do século XX. Também já tinha lido muito sobre a tragédia na chamada “terra santa”, o “dilema” palestiniano, o assalto a esse povo no seu próprio território, A-Nakba, a Grande Tragédia. Viria a saber depois que não era um “dilema”, era uma luta pela sobrevivência, tal como era a de Israel. Hoje já sou um velho, e li muitos dos grandes autores judeus e israelitas e alguns palestinianos, como aliás tenho dado conta nestas páginas. Hoje, vejo a televisão, ouço a rádio e leio os jornais. O terror continua, agora num misto de “entendimento” e revolta, como diria Nietzsche, “demasiada humana”. Receberia um abraço de um judeu, como recebi as palavras de um palestiniano anos mais tarde, por amizade pura e fora de toda esfera política-ideológica, num restaurante que eu frequentava diariamente e de que ele era gerente. Diria agora aos dois: não é uma “terra santa”, é uma terra do “demónio”, e vem de muito longe. Não ignoro o que aconteceu a 7 de outubro de 2023, nem menosprezo a dor dos que foram vítimas desse dia fatídico. Como neste momento não ignoro, não poderia nunca ignorar, o sofrimento de um povo inocente e que luta pela sua vida e pela sua terra em Gaza. Não se trata só de um genocídio, mas de algo indizível na linguagem e terminologia histórica vinda do século passado, aliás vinda desde há muitos séculos por toda a Europa. Bem sei que essa palavra incomoda os que tinham Israel como terra santificada, à força das armas assassinas enviadas pelos Estados Unidos, para a terra de três religiões que são as nossas raízes éticas e também culturais. Só que o crime está à vista do mundo. Há dias ouvi um professor americano a dizer numa televisão internacional que a um Holocausto não se responde com um outro Holocausto. A morte indiscriminada de crianças e de todos os seres inocentes não é aceitável para quem tem a consciência e a noção da nossa comum humanidade. Vingança pura e dura é um ato inaceitável em qualquer circunstância, por mais mortífera que tenha sido.

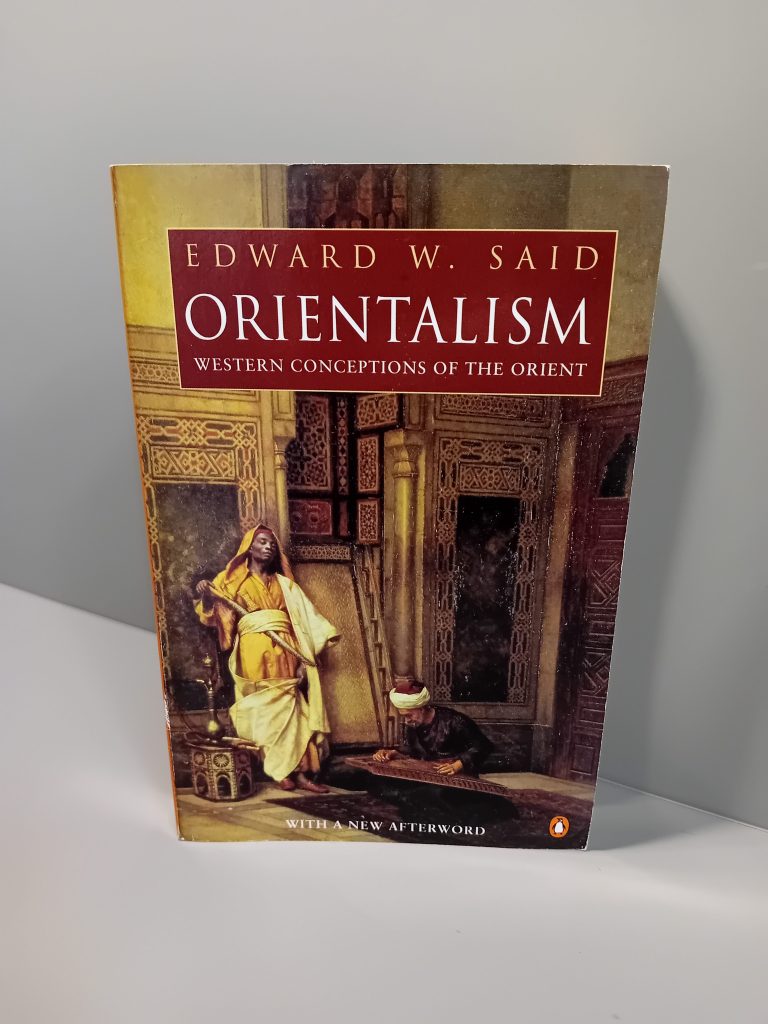

Como não conheço pessoalmente a “realidade” do Médio Oriento, volto aos livros, e leio Edwuard Said, o autor de muitas obras, nascido no Egito, e de identificação Palestiniana. Foi assessor de Yasser Arafat até aos anos 70, quando a Al Fatah começa com atos terroristas. Desligou-se de imediato da sua relação, mas não do objetivo da justa libertação da Palestiniana pela Al Fatah, que pouco mais tarde aceitaria a existência do novo estado vizinho. Sério e genial, professor numa das grandes universidades norte-americanas, a Columbia University, em Nova Iorque, ainda por cima professor de literatura americana. Morreu cedo de uma doença de leucemia. Deixou uma das obras mais avassaladoras, que nos fez reler toda a literatura ocidental, com a obra seminal simplesmente intitulada Orientalismo. Nunca mais leríamos a literatura ocidental com o mesmo ponto de vista. Em leituras profundas desvendaria as imagens que os melhores escritores ocidentais haviam imaginado sobre o “outro”, o colonizado e oprimido tornado caricatura ou filho de um Deus menor.

Que diria ele agora do genocídio em curso na Faixa de Gaza? Muito provavelmente choraria as duas parte no conflito, ele que era também um admirador de todas as artes que representam a nossa humanidade, a que ainda nos resta. Algum tempo antes do seu falecimento juntou-se a um compositor israelita para fundar uma orquestra de jovens judeus e palestinianos, que já não sei se continua a dar concertos para quem queira ouvir. A totalidade da sua obra é imortal – em nome da nossa comum condição, em nome da convivência entre todas as religiões e culturas.

Pois. O Natal. Celebremos. Com a consciência da morte e perseguição dos inocentes. Dois mil anos depois. Ou, como diria um grande poeta e escritor português – o perseguido nunca deve virar-se um perseguidor. Um Holocausto não deve ter como resposta outro Holocausto.

Que dirias agora, Edward Said? Que morreste a ver o teu povo morrer? Que continuas a não encontrar o teu lugar? Ouvirias, por certo, a senhora idosa que há semanas fugia atónita da sua casa bombardeada pelas forças sionistas. Disse no seu choro: “Há 70 anos que nos atormentam. Deus os ajude – e a nós também”. Note-se a sequência das suas palavras e suplício. Filha de um Deus menor? Continuam a morrer. Más notícias para aonde te encontras. Enquanto a nós, como deves saber, suponho, mesmo que nem eu nem tu acreditemos, continuamos a ouvir as canções do Natal. Que compremos coisas. Enquanto a tua gente morre a cada minuto. Na terra santa? Na terra do demónio sempre à solta?

Vambero Freitas–citico literário-Açores

(publicado no Açoriano Oriental)

Christmas 2023: from the “holiness” of the “holy land”

With so many dissonances in my life, I have genuinely learned

to prefer not to be always right and marginalized.

Edward W. Said, Out of Place

It’s Christmas for Christians and for many others who celebrate it out of respect or because of beliefs very close to our own. As for the epigraph, I will identify the author and his words in other lines of this piece. The reality is that the world is at a terrifying boiling point – war everywhere, famine, persecution, death. Nature itself is in revolt. Allow me to say a few words about myself. In 1973, the Yom Kippur War took place, in which several Arab countries attacked Israel – which had been founded by the will of much of the world – to wipe the relatively new country off the map. I was still attending college daily at California State University, Fullerton, as a student majoring in American literature.

At the time, Portugal was a very distant country for me, and now and then, I would look at my Portuguese ID card. I no longer recognized myself, not even my past, after leaving the Azores at the age of 13, and when I did, I felt ashamed of what was happening in Africa, even with the bit of information I got from the press. I had read that all of Europe had vetoed the flight of American fighter jets to help Israel in a war that they said was “unequal.” Portugal had been the only one to cooperate when it gave up the Lajes Base to help the country under attack. At the time, I thought it was a gesture of solidarity with the Jewish state. Until I learned that we had been pressured by the late Henry Kissinger in his usual blackmailing manner towards this poor ally with no power due to its hazardous “defense” on the colonial issue.

One day, I was walking through the grounds of my university during the fighting in the Middle East, which I didn’t pay much attention to, and an unknown colleague got up from a group sitting on a bench with a broad view of the campus. He introduced himself and said: we’ve been told you’re Portuguese and from the Azores. I looked at him with a certain amount of suspicion and bewilderment. Can I hug you, he asked me. Yes, I said, still a little suspicious. He hugged me and said in a low voice: Thank you to your country and your islands for allowing us to help Israel. I shrugged and said nothing else but didn’t know what he was saying to me in detail. I’ve never forgotten that moment. Despite everything, I felt proud of myself. I don’t know for what. At that time, everything concerning Israel in the United States was blindly supported – I thought. Israel was a kind of holy country; the wounded conscience of the United States said little to me, knowing that they had done very little to save the persecuted throughout Europe during the ongoing persecution and Holocaust by the Nazis.

I had already read a lot about the Holocaust of the 20th century. I had also read a lot about the tragedy in the so-called “holy land,” the Palestinian “dilemma,” the assault on these people in their territory, A-Nakba, the Great Tragedy. I would later learn that it wasn’t a “dilemma.” It was a struggle for survival, just as Israel’s was. Today, I’m an older man, and I’ve read many of the great Jewish and Israeli authors and some Palestinian ones, as I’ve written in many of my essays and books. Today, I watch television, listen to the radio, and read the newspaper. The terror continues in a mixture of “understanding” and revolt, as Nietzsche would say, “all too human.” I would receive a hug from a Jewish young man, as I received words from a Palestinian years later, out of pure friendship and outside of any political-ideological sphere, in a restaurant I frequented daily and of which he was the manager. I would now tell them it’s not a “holy land.” It’s a land of the “devil,” which goes back a long way.

I don’t ignore what happened on October 7, 2023, nor do I belittle the pain of those who were victims on that fateful day. Just as I am not ignoring, and could never miss, the suffering of innocent people fighting for their lives and their land in Gaza. This is not just a genocide but something unspeakable in the language and historical terminology of the last century, which has been used throughout Europe for many centuries. I know that this word bothers those who had Israel as a sanctified land, by force of murderous weapons sent by the United States to the land of three religions that are our ethical and cultural roots. But the crime is there for all to see. The other day, I heard an American professor saying on international television that another Holocaust does not answer a Holocaust. The indiscriminate killing of children and all innocent beings is not acceptable to anyone who has a conscience and a sense of our shared humanity. Pure and complex revenge is unacceptable, no matter how deadly it may have been.

Since I don’t know the Middle East’s ” reality, ” I turn to books and read Edward Saíd, the author of many works, born in Egypt and of Palestinian identification. He was an advisor to Yasser Arafat until the 1970s when Al Fatah started committing terrorist acts. He immediately disassociated himself from their relationship, but not from the goal of the just liberation of Palestine by Al Fatah, which would later accept the existence of the new neighboring state. Serious and brilliant, he was a professor at one of the great American universities, Columbia University in New York, and a professor of American literature. He died early of leukemia. He left behind one of the most overwhelming works, which made us re-read Western literature, with the seminal work entitled Orientalism. We would never read Western literature from the same point of view again. In deep readings, he would unveil the images that the best Western writers had pictured of the “other,” the colonized and oppressed, who had become caricatures or children of a lesser God.

What would he say now about the ongoing genocide in the Gaza Strip? He would probably weep for both sides of the conflict. He was also an admirer of all the arts that represent our humanity, the one we still have left. Sometime before his death, he teamed up with an Israeli composer to found an orchestra of young Jews and Palestinians, which I don’t know if it still gives concerts to anyone who wants to listen. His entire oeuvre is immortal – in the name of our shared condition and coexistence between all religions and cultures.

Yes, it is Christmas. Let’s celebrate it. With an awareness of the death and persecution of the innocent. Two thousand years later. Or, as a great Portuguese poet and writer would say – the persecuted should never become the persecutor. Another Holocaust must not answer a Holocaust.

What would you say now, Edward Saíd? That you died watching your people die? That you still can’t find your place? You would certainly listen to the older woman who, weeks ago, fled in astonishment from her house bombed by Zionist forces. She cried: “They’ve been tormenting us for 70 years. God help them – and us”. Note the sequence of her words and her torment. Daughter of a lesser God? They keep dying—terrible news if you are one of the martyred people. As for us, I suppose we will continue to listen to Christmas carols even if we don’t believe in them. Let us buy things! While your people die every minute. In a holy land? Or in a land of the devil, who seems to always be on the loose?

Vamberto Freitas, literary critic (translation by Diniz Borges)

São Miguel, Azores (initially published in Portuguese in Açoriano Oriental newspaper)

____