Dias de Melo’s Impact on Azorean Literature

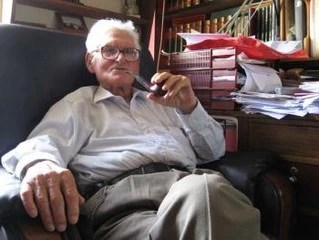

José Dias de Melo (1925-2008) is one of the few writers from the Azores known nationally, not only because of the number of books he wrote and published but also for how often he did so and, above all, because he chose subjects that only he knew how to build upon, touching the most profound and universal human traits, using the Azorean reality. Therefore, Dias de Melo is a cornerstone writer in Azorean cultural production and, thus, essential for whoever wishes to understand the literature currently created by Azorean writers.

Dias de Melo’s literary work was built upon two main parameters. The first concerns the ordinary everyday citizen and the living cultural experiences. He was able to document the relationship of life and death, presence and absence, love and hate — which, for centuries, Azoreans established with the sea, their daily partner; the second is ruled by the writer’s need to reflect on his condition as an islander and a writer, projecting his writing knowledge and experience: when he mentions whalers, emigrants, or writers, Dias de Melo bases his work on what life has taught him — using an admirable narrative technique, a linguistic freshness that doesn’t give in to folkloric ease or regionalisms, a simple authenticity of the human types he recreates, therefore updating the living echoes of that telluric past, way beyond the islands’ colonization, where, as Nemésio guaranteed, Azorean life is spiritually projected.

Amongst his vast literary work, one must emphasize Dark Stones (1964), a life narrative, labor, and death of two defeated heroes — Francisco Marroco and João Peixe-Rei — written in a register appropriate to the awakening times Portugal lived through in the 1960s: the islands’ chronic poverty joined with the news of soldiers lost in the colonial wars, with no end in sight, which fueled a new wave of emigration towards America — not by jumping onto the whaling boats towards New Bedford, like before, but by the US Family reunification Act (Cartas de chaamda) or with a “tourist” visa to the dairy farms of California.

When we talk of Dark Stones, we mean Azoreanity or Azoreanness, specifically Pico Azoreanness, which is the same as saying the soul of a hardy people that never let themselves soften by centuries of “hunger, droughts, cyclones, volcano fire, earthquakes,” surviving on an island of dark stones from hence, one always yearned to leave (because “the island rejects people”), and to which one always yearns to return (because “the island beckons people”) — in a relationship of life and death, presence and absence, love and hate, prosperity and bankruptcy, dreams and nightmares about the sea — that daily companion, sometimes opening the routes of the world, sometimes a tomb for man’s dreams (like João Peixe-Rei, whose death in the far-away Cape

Horn is one of the narrative’s highest and most heartfelt moments). An Azoreanness, with Francisco Marroco as its paladin, he who ran away from a hunger-ridden childhood by jumping into an American whaling ship, thus sailing the world seas and then, through America, making a living, which would eventually bring him back to the island and die there, not without first visiting his son, António, in prison, where he was sent for nothing more than denouncing the abuses of capitalism — still incipient, although already triumphant — which would forever transform the old art form at which Pico men were so skilled, of mixing land work with whaling at sea…

Dias de Melo, on the path of this good tradition of men of two different crafts, mixed his experience of a profound connoisseur of the life, suffering, and death of whalers — let us remember his monumental collection of whaling-related narratives, published in several volumes with the title Na Memória das Gentes (In People’s Memory) (1985-1991) — with his experience as an abundant and versatile writer who also reflects upon his condition as an author, which legacy he left us in the novel O Autógrafo (The Autograph) (1999) and, above all, as an honest hard-working man who, in an intense moment in his life, decided to reflect upon his life and work — for example, in the novel Milhas Contadas (Counted Miles) (2002). The expression “counted miles,” collected from the heroes of the Azorean sea, signifies nearing the end of the journey, with land in sight, and our heroes — may they be Pico whalers, the writer who composed their epic journeys, or Pedro António, this novel’s protagonist — is back, bringing back with them a whole life story to tell those who never got away from the Island. Also, more trivially, counted miles are the poems, the novels, the tales, the chronicles, the ethnographical collections, or the monographies that Dias de Melo conceived and published throughout sixty-four years — and represent, by themselves, at least two lives: a talented, hard-working, passionate writer’s life, and the collective life of Pico’s people, who are, deep down, the real reason of being of Dias de Melo’s work. Mile by mile — i.e., book by the book — Dias de Melo built what is, from many points of view, among which “authenticity,” one of the unique works of Portuguese literature of recent years.

From the translated in the Azorean Encyclopedia, revised by Diniz Borges

Dias de Melo describes his writing…

“I am a writer. Portuguese, because I’m a citizen of Portugal, my country. Azorean because I’m a citizen of the Azores. However, I’m a writer from Pico – my Island, my home. And, because I’m of the People – of the People from my Island, our Island, my home, our homeland, many of my books take place on our Island, our homeland. Most of the characters in them are modeled after the People, our People. With their virtues and their faults, their love and their hate, their affections and their aversions, their dedication and their indifference, their solidarity and their hostilities, their loyalties and their betrayals, their heroic trajectories and their cowardice acts. In short, their angels and their demons. Those same angels and demons are an intrinsic part of all human beings. Even of saints.”

Dias de Melo

Window where Dias de Mello did much of his writing on Pico island

You can get the book Dark Stones translated into English through our friendds at Tagus Press.

a brief video for those who understand Portuguese on the life and the writings of Dias de Melo