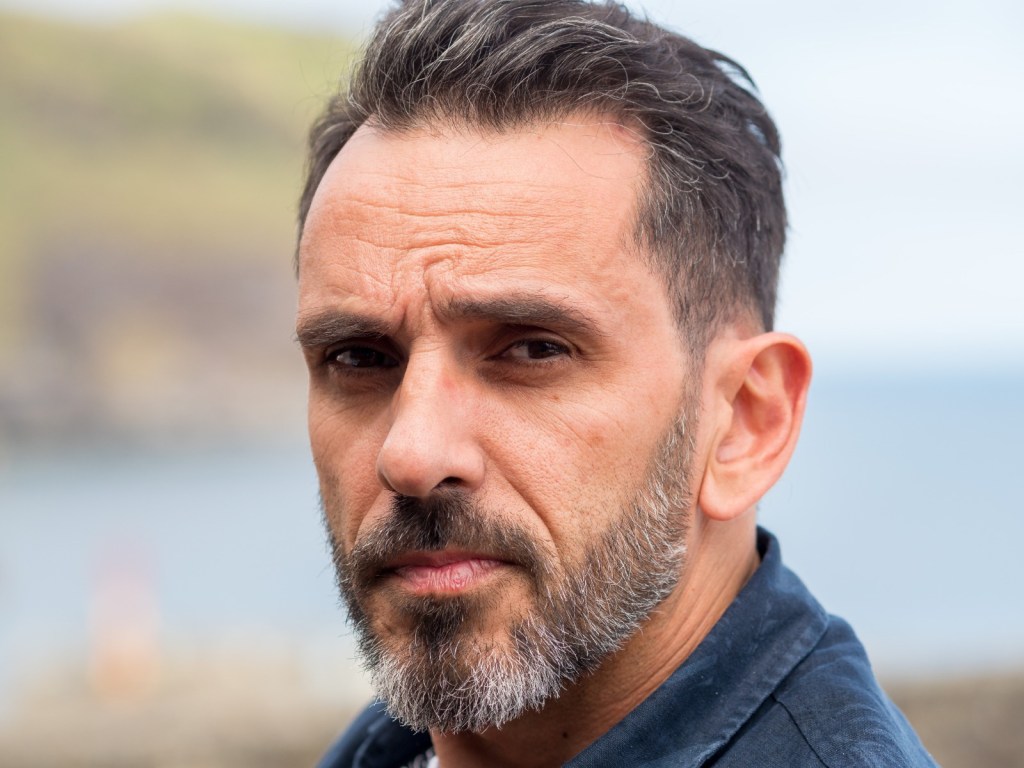

Rui Melo is an Azorean artist resident in Terceira Island. He has regularly held exhibitions in Portugal and abroad. Living on a volcanic island has made him acutely aware of the precarious balance of human existence in the face of the forces of Nature. This precariousness is reflected in his work by the importance given to the randomness of chance as an inherent process of Nature, by the telluric side of the spots that liquefy, expand and explode, splashing blue – the predominant color of his paintings sometimes punctuated in red – the support. The use of virocco as a support and the exploration of the nuances it allows, sometimes leaving its irregularities visible, creates a markedly materic texture, summoning a synaesthetic perception that characterizes his painting. In this interview, Rui Melo tells us about his creative process and how his experience is reflected in it, focusing in particular on the series of paintings Transversal Landscapes, 2017, and its relationship with the pictorial tradition of the landscape.

How is your creative process? Do you draw first, get inspired by textures, or start by experimenting with materials?

The process almost always starts with experimentation with materials. However, there is a basic idea as a starting point. But it is the way the materials react to each other that often guides the process. Knowing how to act at the right moment is essential while leaving the critical part of that reaction unchanged.

You like to incorporate chance and the unpredictability of materials into your paintings…

Yes. The question of chance itself is something I work with. I see chance and unpredictability as “tools”. The final result is a bit of an image of that. Those who observe them realize that confrontation has several elements, and the end of that story is not determined in advance. Of course, some techniques are developed to optimize results, but this unpredictability and the question of chance are determining factors.

Since 2009, you have been using viroc as a support, which allows a more material texture of the painting that summons an almost synesthetic perception. Is it intentional?

Since 2009, the use of viroc (the commercial name of wood and cement composite panel) started from an immediate empathy with its texture. My relationship with the material was very visual, and I found it integrated well with my actions. The patinas and their different nuances interested me. All the work on viroc was done to leave much of the material in its pure state because it has an irregularity that I wanted to be part of the composition by combining its own stains with the composition created. The challenge was often to leave areas of the support immaculate.

In Toiro I and II you used this hiding technique and unhiding the support.

These are two photographic works that were made for an exhibition on bullfighting, and when we look at them, they have a lot in common with my painting work. The material used and the technology were different. The underlying concept, in essence, would be to express through that skull of a bull what remains of bullfighting after the party and the human satisfaction. All the plasticity is related to my painting process. Specifically, a photograph was made on a white background, digitally treated so that the pictorial character of those bones would stand out.

fig. 1 – Rui Melo, Toiro I, 2006, 60 x 60, fotografia. Coleção particular.

fig. 2 – Rui Melo, Toiro II, 2006, 60 x 60, fotografia. Coleção particular.

Is the tension between the materials in your paintings, sustained by a precarious balance, which Carlos Bessa mentioned, something you seek? How do you know that you have reached this balance, that is, what is the moment you consider the painting finished?

As I mentioned, my creative process can be particularly chaotic, making knowing when to stop the most crucial question. In this kind of work, there are never absolute certainties; that’s where artistic sense and sensitivity are most needed. When we feel we have reached the limit point beyond which nothing can be added, we try to fix it. That is the great riddle to solve: the right moment to stop. This knowledge happens when you feel empathy with the composition. The precarious balance question, that tension created in the works that Carlos Bessa talks about, is fundamental in my work. The work itself is an object of communication; it must appeal to the viewer: this tension, if well worked out from a compositional point of view, will awaken an appeal. I understand this factor as a constituent element of the composition.

How did you come up with the idea of transversal landscapes?

The question of transversal landscapes has much to do with the previous question. Perhaps my islander side manifests itself here, but it could be from here or from any other part of the Earth. When you live in a place with these characteristics, with its telluric strength, you have an evident notion of your fragility and smallness. You have the ocean before you, a volatile sky above you, and fire under your feet. It is not easy to be indifferent or challenging to face Nature humbly.

So we are very close to these elements, apparently opposed to each other. This precarious balance ends up, in a way, being reflected in my works. The question of the transversal landscape is related to this experience. I called them “Transversal Landscapes” in an ironic inversion… as if instead of the classic concept of landscape and the horizontality that underlies it, we made a vertical cut. In doing so, what we would find underneath us would surely be as fascinating as what we see in the horizontal section. The transversal landscapes are related to what we don’t see, but on which we walk and which we often don’t even realize, even though it is so powerful and can change from one second to the next, showing how our passage on Earth is simply an instant of luck (or not)… In the end, it is something telluric, something about the Earth. Not about these islands specifically, but about the Earth and human fragility.

Fig. 3 – Rui Melo, Paisagem Transversal V, 75×122 cm acrílico e tinta da china sobre tela 2016 col. particular

As a genre, the landscape was born with the idea of Cartesian rationality and man as active, a fixed and rational look at an available nature associated with women. In your paintings, on the contrary, it is the materials that “speak,” and Rui Melo tries to be a good conductor…

My perspective on the notion of landscape is not conventional. I call them “landscapes”, but I could call them something else… I haven’t found a term that better defines what I do. But it seems to me that your interpretation is pertinent, and I understand that, in a way, this philosophical association with women, also in this case, will not be out of place.

What are the advantages and added value of living on an island for your activity?

Apart from the conceptual dimensions mentioned above and a different quality of life from urban environments, from a practical perspective, there are no added values as a visual artist who needs to exhibit and make his work known. Nevertheless, as a native, the choice of the island was not difficult. Living outside it would not be easy. I believe that this experience gives me a very particular view of the world, which I try to reflect in specific works without them becoming, as I have already mentioned, a regionalist perspective that I find uninteresting. I try to fix that substance arising from this unusual experience. Some logistical constraints have to be overcome, but they are not insurmountable. They can be costly, particularly when it comes to transporting them.

What other things inspire you besides Nature, which is undoubtedly impressive? Are you inspired by other artists or readings?

Yes, several artists have marked my way of working. In a somewhat disturbing historical leap, I could say, from Bosch and Caravaggio, through many other unavoidable ones, to, for example, Helena Almeida. Although it may not be apparent, these universes seduce me differently. I was lucky enough to see the work of some of these artists live, which left a strong impression on me. Basically, my work is the result of my experience and the influence of these painters. If I could indicate a painter I can give as a favorite, I can not answer… Yes, I consider the knowledge of the History of Art fundamental in constructing a proper and consistent language of any artist.

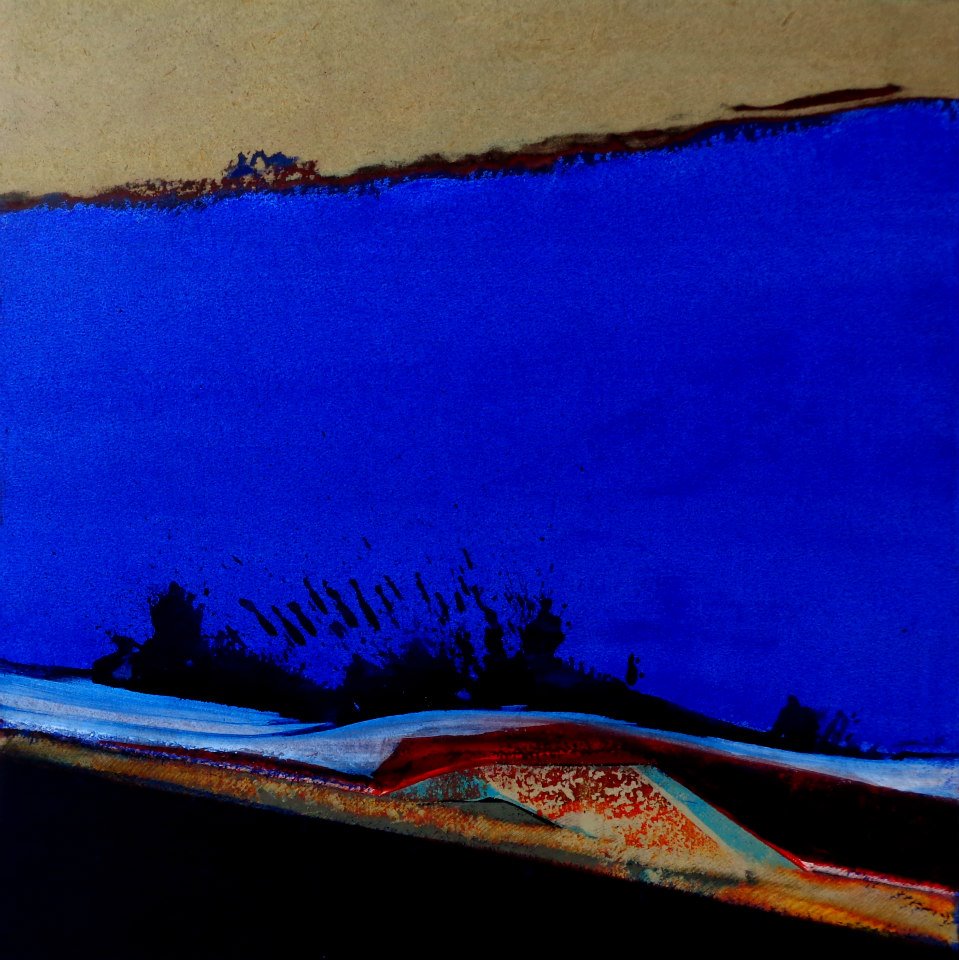

In this series of transversal landscapes, do you prefer blue, a particular type (ultramarine?), or is it the presence of the sea?

There was a phase, which I think has not yet ended, in which ultramarine blue was predominant. I can’t say precisely if it’s the presence of the sea. I find it difficult to isolate the elements of my work because things flow. It’s a bit irrational, but you can make a natural connection that way. Whether we like it or not, this is a powerful mark. This force gives direction to our experience and work, and I think it is legitimate to interpret it that way, although in many cases, it may not have such a direct connection.

Fig. 4 – Paisagem Transversal VIII, 30×30 cm, acrílico e tinta-da-china sobre tela, 2016, Galeria ACERVO

…but the horizon is absent. It is, therefore, an immersion in the landscape; this aspect is also not the traditional one in the landscape that presupposes a distance…

It is a good observation. It is an approach to the landscape that is not conventional, and when I give it that title, it also has this almost provocative dimension since it is evident that there is no horizon line in many paintings. In some cases, there may be a suggestion, but it is often vague and tends to enter a dimension of what is not known and what is not directly seen, but it is, as you say, somewhat immersive. That world interests me far beyond what is merely visually perceived. These landscapes are, in fact, landscapes that I do not see from an optical point of view. They are landscapes that I feel. The question of the absence of the horizon line is somehow linked to this idea, and they do not give it the traditional dimension as if they were landscapes from a romantic point of view or a Turner that, even without an explicit horizon line, are wrapped in a fog that, being diffuse, persists in being figurative. And well. In my case, it is not so because these are immaterial landscapes.

The sublime concept may have something to do with it because, as Kant defined it, it does not exist outside of us; it is a feeling of smallness before the forces of Nature. Does the sublime mean something to you, or is it too romantic?

Your question is interesting. Despite being a particularly romantic concept, the question of the sublime is present in my work, albeit with the natural formal distance. In a way, the question of “transversal landscapes” deals with this concept in a particular way, which involves the awareness of one’s own dimension in relation to a force that is uncommonly greater.

Did you also use the photographic technique in Landscapes I and II from 2002?

These works, like the others that follow them, have photographic parts. They are related to the work I did while at university, in which the question of photography was interspersed in an experimental way with painting. It was a combination of disciplines. It was a dimension that I wanted to experiment with and was part of an investigation into some materials and stamping processes. I experimented with how much painting and photography could converge in the same direction. And, in fact, in those years, I have several works made on paper with stamping photographic images and painting.

This interview is from the site Arquipélagos Criativos—here is the link to read it in Portuguese

http://arquipelagoscriativos.unidcom-iade.pt/?page_id=186

This news story was translated to English as a community outreach program from the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI) and the Modern and Classical Languages and Cultures Department (MCLL) as part of Bruma Publication and ADMA (Azores-Diaspora Medial Alliance) at California State University, Fresno.

Some other works from Rui Melo (from his facebook page)

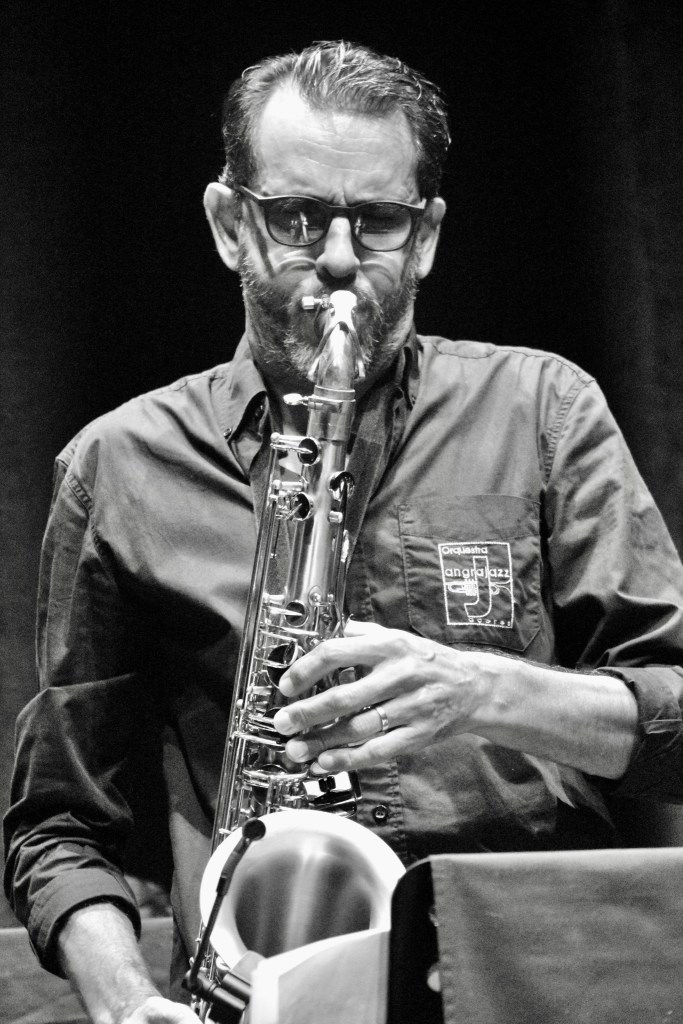

Rui Melo is also a very talented musician…Filamentos will cover that facet in future publications

As a Graphic Artist he has designed book covers for Bruma Publicaitons and our PBBI-Cátedra Natália Correia Logo